My Toxic Reality: The Fight for Environmental Justice / Ralph Nader and Hilton Kelley

“Nobody really wants to leave their community and I don’t blame them because it’s our culture and we shouldn’t have to move just to have clean air to breathe. That should be God-given right to drink clean water, to breathe clean air.” -Hilton Kelley

During the modern environmental movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s, landmark legislation was passed in the U.S. to ensure cleaner, safer air and water across the nation. But in recent years it’s been difficult for environmental policies to get through Congress. That leaves activists having to turn their energy away from Washington and instead focus on grassroot movements to create local change.

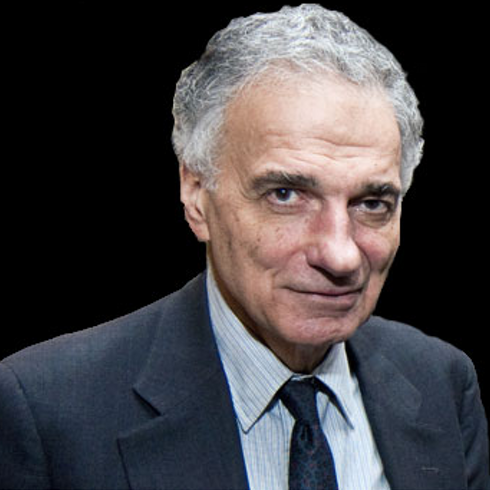

In this bonus episode, we will hear from Ralph Nader, a consumer activist and former presidential candidate, and Hilton Kelley, who is fighting to clean up his hometown of Port Arthur, Texas by empowering the community to demand cleaner air. This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Hilton Kelley: “And we’ve come to realize that, you know, it is what it is and this is my home. I can’t afford to go anywhere else. Nobody really wants to leave their community. And I don’t blame them because it’s our culture and we shouldn’t have to move just to have clean air to breathe. That should be a given, a God given right to drink clean water, to breathe clean air.”

Céline Gounder: Hi, Dr. Celine Gounder here, the host of the show American Diagnosis, the podcast about health and social justice.

During the modern environmental movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s, landmark legislation was passed in the U.S. to ensure cleaner, safer air and water across the nation. But in recent years, with bipartisanship hard to come by, it’s been difficult for environmental policies to get through Congress. And under the Trump Administration, many key provisions have been reversed or removed. That leaves activists having to turn their energy away from Washington and instead focus on grassroot movements to create local change.

During this bonus episode of American Diagnosis, to better understand this shift, we will hear from Ralph Nader, a consumer activist and former presidential candidate, who 50 years ago was instrumental in passing major environmental policies by lobbying lawmakers on the hill. To the new strategy of today – where activists are less focused on politicians, like Hilton Kelley who is fighting to clean up his hometown of Port Arthur, Texas, by empowering the community to ensure and demand cleaner air.

Céline Gounder: To start this episode let’s begin in the early 1970’s when major environmental laws such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Environmental Protections Agency or EPA, were put on the books.

Archival Tape of Ralph Nader:“Millions of people in the United States breathe the pollutants that give them cancer, that give them emphysema, and other forms of lung disease – by what right?”

Céline Gounder: During this time period, Nader was a force for consumer protections – not just on environmental issues though but on everything. He was instrumental in getting seat belts and airbags put into cars, smoking banned from airplanes, to an FDA ban of the carcinogenic red food dye. But in order to explain Ralph Nader’s role in all this, particularly on environmental policies – we will have to go back to his childhood.

Céline Gounder: Nader grew up in a working class town in Connecticut, called Winsted. His parents, Nathra and Rose, settled there after immigrating from Lebanon as young adults. After working at the local textile mill, his father opened up a restaurant and bakery in town where Ralph and his siblings spent most of their days.

Ralph Nader: We had a real communion with people who were trying to make a living in the country.

Céline Gounder: That’s when his passion for consumer protections first took root. But it was his upbringing that really put him on the path of activism, which was modeled by his mother Rose. Her fight was taming the Mad River, which ran through their town.

Ralph Nader: The Mad River was well-named and it flooded about three major times. In the 20th century, up to 1955, it’s a big flood with Hurricane Diana and it killed 11 people and destroyed half of main street. And it was a mess. And my mother was pretty fed up because there was a 1937 flood that did the same thing. It destroyed our restaurant. And there was always talk about a dry dam and nothing ever happened.

Céline Gounder: But Nader’s mother wasn’t going to sit around and wait. So when she heard that one of the Connecticut Senators, Senator Prescott Bush, father to President George H.W., was going to be in town campaigning – she made sure to show up.

Ralph Nader: She went to the gathering and stood in line and stood in line. She finally got up to him, grabbed his hand and said, ‘Senator Bush, you’ve got to make the dry dam. And you’ve got to get it done. We can’t have another flood,’ and he smiled the way politicians do and started extricating his hand to shake the next hand and she wouldn’t let him go, she wouldn’t let him go (laughs). And people were a little bit embarrassed, waiting. And he finally said, I’ll do it. And he actually did it and we built the dry dam and there’s never been a flood since.

Céline Gounder: Growing up in a mill town, Nader was used to the polluted waters and dirty air. It was the way things were back then.

Ralph Nader: We never grew up even thinking that we could wade or fish in them. They smelled bad too and looked bad, they looked like rainbows. And we went to a school called central school and right next to it was a rendering plant of chickens and the smell was horrible. And a lot of it was preventable. They just used our air and water as sewers. I mean, it’s just a normal thing to do.

Céline Gounder: But Nader didn’t think much about this pollution until after he graduated from Harvard Law School when he began his crusade for consumer protections. This fight included the automobile industry, healthcare, pension system, insurance to the environment. When he took on these conglomerates – he did so ferociously and passionately, never sugar coating the issue.

Archival Tape of Ralph Nader:“The laws are very weak, the penalties are even weaker. Picture the scene – you can destroy a body of water like Lake Erie and nothing happens to any of the polluters. You can destroy a beautiful spot on the West Coast called the Santa Barbara OffShore Area and there hasn’t been any criminal prosecution or fine of the violators. There was recently a million dollar fine imposed on Chevron for the biggest oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico – what is that? That is nothing. That is about an hour’s gross revenue for the company.

Céline Gounder: Nader’s environmental work took off in the late 60’s when new organizations such as the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth to Greenpeace put a national spotlight on the issues around water contamination and pollution. But the strategy wasn’t just to make noise, it was also very politically focused.

Ralph Nader: We didn’t just have rallies around the country where the energy went into the ether on a weekend, we focused on the place where the decision could be made. And if you got laser beam advocacy groups to take the rumble from the people and focus it on the House and Senate one by one and feed the material back home so that the rumble became more, the demonstrations and the pickets and so on. And in just a matter of three years, we got which what we could not get in the succeeding 45 years.

Céline Gounder: This strategy was effective – but it was only made possible because of the political climate at the time under – of all Presidents – Richard Nixon.

Ralph Nader: Nixon was the last Republican to be afraid of liberals. He saw mass demonstrations in Philadelphia and New York and Los Angeles and Chicago, where there were Republicans there. And then Earth Day came along. It was 1970. 18 million people participated in thousands of events on April 22, 1970. That totally freaked him out. So you see, the rumble from the people really can affect even the most retrograde politicians.

[archival tape of the first Earth Day]

[(music) As much aroused by the music as the damage done to the environment. This is Philadelphia on Earth Day. ‘Welcome Sulfur Dioxide, hello Carbon Monoxide (fade out).]

Ralph Nader: And Nixon was so freaked out that he signed anything. He signed the Environmental Air Pollution Control Act, the Clean Water Act. He set up EPA, set up the Environmental Council in the White House.

Archival Tape of President Richard Nixon: Clean air and clean water, the wise use of our land, the protection of wildlife and natural beauty, parks for all to enjoy. These are part of the birthright of every American. To guarantee that birthright we must act and act decisively. It is literally now or never.

Céline Gounder: But when it came to enforcement, it was a real battle. A battle that is still playing out today in communities across the country.

Ralph Nader: And so the lobbies from the corporations flooded Washington and, you know, they outnumbered environmental lobbyists by a hundred to one. You go to the EPA, they filled the corridors and they made sure that the budgets were very, very minimal by lobbying Congress. And so there, there weren’t many prosecutors, investigators, scientists developing updated standards, revisions, educating the public, involving the public, in the rulemaking process.

Céline Gounder: But since politics have become so polarized, this kind of across the aisle work is almost unimaginable today. Since President Trump took office, many of the environmental policies passed by former President Barack Obama have been slashed.

Archival Tape of Donald Trump:“So Obama is talking about all of this global warming and that, that, that – it’s a hoax, it’s a hoax, it’s a money making industry. It’s a hoax.”

Céline Gounder: Given the state of politics today, Nadar’s lobbying focused strategy doesn’t seem to be working as effectively. His advice – is go after the big corporations – sue for wrongful injuries and harm. And more importantly empower residents to self regulate their own communities to ensure clean water and air for their towns and cities.

And that’s exactly what activist Hilton Kelley of Port Arthur, Texas is doing.

More on that after the break.

* * *

Hilton Kelley: (driving noises) Okay. What I’m going to do now is we’ll start the Port Arthur toxic tour with just a sort of lay of the land and a little history of the downtown area.

Céline Gounder: Hilton Kelley grew up in Port Arthur, Texas – home to Motiva, the largest oil refinery in the country. It’s a city surrounded by local refineries and chemical plants – an industry that hurts and helps the community at the same time. We asked Kelley to show us around.

Hilton Kelley: And then we’ll head into the historic African-American community in West Port Arthur. And take a look at the refineries, chemical plants and how the community is right up against their fence line. (blinker noises)

Céline Gounder: In the early 1900’s Port Arthur was a booming oil town. This new industry created lots of jobs and uplifted the economy. When Kelley grew up in the 1960’s – the city was alive. Sailors from all over the world would flood the port, famous artists from Ray Charles to Aretha Franklin would perform at the local theatre and the downtown was vibrant with thriving stores and shops. Now – that local theatre no longer exists and many of those bustling downtown shops on Proctor Street — have been torn down.

Hilton Kelley: This was really the place to be. And so as we move further down Proctor and you look right to left, what you see is another vacant lot. Here is the Sabine Hotel to my left, here on the corner of Waco and Proctor. And it’s been dormant, dilapidated, falling apart.

Céline Gounder: As wealthier families began to move away from the city, they took businesses with them. Meanwhile those who couldn’t afford to leave, a majority African American, were forced to stay. Today – more than a fourth of the population lives below the poverty line. And the city has one of the highest unemployment rates in the state. With few jobs in town – the biggest and highest paying employers – are the refineries.

Hilton Kelley: If you’re not working at a plant, then you’re making maybe minimum wage, which in some cases here in Port Arthur is like $8, $9 an hour. If you’re working at one of the plants, starting out you are gonna be making at least $18 to $19 an hour. So that’s a big jump. And this is why so many people have a desire to work at the plant. Even though in this day and time we understand the dangers, we understand what the odors are, we understand that sometimes things happen like explosions, but many folks are willing to take that risk to put food on the tables for their families.

Céline Gounder: But the industries that provide these families with a living wage are also the ones harming them.

Hilton Kelley: And this area, sometimes it really, really has a very strong, pungent odor of sulfur. And when you breathe it in, it stings your nose. It constantly makes you want to try to clear your throat. And every now and then when there’s a fire or a stack needs to be lit, that heavy soot or smoke pours right into this community. We have a large number of people in this community with respiratory problems like asthma, bronchitis, one out of every five kids in this community have to use a nebulizer. And take breathing treatments before they go to sleep at night or before they go to school. We have a large number of people here with cancer that have died and some still suffering.

Céline Gounder: The gravest health effects are in West Port Arthur, the predominately African American and low-income section, where Kelley was raised. The West Side’s asthma and cancer rates are among the highest in the state.

Hilton Kelley: As we continue down 14th street, I just want to make note that we are traveling parallel to the Motiva Oil Refinery. And at the end of West Port Arthur sits the Valero Oil refinery, Chevron Chemical, Oxbow Calcining, Petko Facility.

Céline Gounder: Besides many of the houses – the local schools are also right next to the refineries and chemical plants.

Hilton Kelley: Now this is Booker T Elementary School. And if you notice, Booker T Elementary sits there and the oil and gas industry is only like maybe four city blocks away from that school. And by theory, the Environmental Protection Agency states that no schools should be within a two mile radius of an oil or gas industry, but there’s no way in the city of Port Arthur where a school cannot be within a mile radius. So the only way you would achieve a two mile radius is by putting the schools out in the Sabine Lake or out in the Gulf, and that’s not going to happen. (laughs)

Céline Gounder: Growing up – Kelley used to get such bad headaches that he had to take medicine and lie down until it wore off. For many, many years people like Kelley were being subjected to tons and tons of toxic chemicals such as sulfur dioxide, ammonia, carcinogens like Benzene and 1,3 Butadiene, which can cause irritation in the lungs and eyes, chronic headaches, heart problems, reproductive issues and even cancer. Kelley had no idea the harm or more importantly the laws and regulations against it. According to the EPA, Port Arthur has some of the highest levels of toxic air releases… in the country. But Kelley didn’t think much about it.

Hilton Kelley: One time Port Arthur West End and downtown Port Arthur was a booming place to be. And yet everybody just sort of, you know, accepted the fact that the air here, it smelled like rotten eggs most of the time. It was just a way of life. It is just the way it was.

Céline Gounder: And when he graduated high school – he left Port Arthur and joined the Navy. He was stationed in Oakland, California. But when he got out of the service he stayed in California, raised a family and spent 13 years in the acting industry. From time to time, he would come home to visit.

Hilton Kelley: When I came back to port Arthur, Texas in 2000, I came back here initially just to go to a Mardi Gras visit with friends and relatives, and, as I walked around Port Arthur, I was just kind of disgusted with what I saw.

Céline Gounder: But Kelley couldn’t get what he saw – off his mind. So a few months later, he decided to move back and help change things.

Hilton Kelley: I kept thinking about the condition of my hometown and what people were dealing with, and the number of people that I grew up with that had died from cancer. Most of the time, whenever anybody passes here in the city of Port Arthur from what they call natural causes, well, it’s cancer or respiratory related. Uh, many people here suffered in disproportionate numbers with respiratory issues, cancer issues and skin disorders as well. And I think it’s because, largely in part because, of what we’re being subjected to when it comes to toxic fumes that we have to breath in and the ambient air that’s around us all the time.

Céline Gounder: But many of the residents in West Port Arthur don’t have a choice.

Hilton Kelley: But we’ve become kinda complacent. And we’ve come to realize that, you know, it is what it is and this is my home. I can’t afford to go anywhere else. So I’m going to maintain what I have, I’m going to do the best of what I have. And if you look at many of these homes, these are really, really nice homes. Nobody really wants to leave their community. And I don’t blame them because it’s our culture and we shouldn’t have to move just to have clean air to breathe. That should be a given, a God given right to drink clean water, to breathe clean air.

Céline Gounder: Kelley’s background was in acting – he knew nothing about environmental regulations or laws such as the Clean Air Act that Ralph Nader helped pass. And had zero experience in community organizing. But he was eager to learn to help his community. So he asked around and got in touch with those who were already trying to clean up the pollution in town.

He met all kinds of people including one guy who showed him how to capture and test the air for toxins using just a store bought bucket. It looks like a middle school science project…but it works. Plus it’s cheap, easy and approved by the EPA. The device involves a 5 gallon bucket with two valves on top, one to suck the air out of the bucket creating a void where the air inside will flow into the plastic bag attached to the second valve. The air in the bag is then sent to a local lab and tested for toxins.

Hilton Kelley: And once it was proved to me that we were being exposed to benzene 1,3 butadiene, high levels of sulfur. I was just floored because we would get back results showing that we had, uh, like maybe 10 parts per million of sulfur dioxide or 20 parts per million of benzene, which was really outrageous. And, uh, that’s what really sort of lit the fire under me to push me to advocate for a cleaner, healthier environment and reduction of emissions from these facilities.

Céline Gounder: Now Kelley had the knowledge and tools to take on these big oil and gas industries, so he took the fight to Washington and even brought his 5 gallon bucket with him.

Hilton Kelley: I went to Washington, D.C. back in 2002 and I spoke before the U.S. Senate and I brought one of the buckets with me – the five gallon paint buckets, that is our grab sample device. And I brought it onto the Senate floor. And when I was speaking, I demonstrated to them exactly how we grabbed air samples, and I educated them on the high levels of pollution that many citizens in Port Arthur and the area are exposed to.

Céline Gounder: He also established his own organization called the Community In-power and Development Association (CIDA), and began training local residents to monitor air quality.

Hilton Kelley: We partnered with people from all over the country. We would stage many, many protests from Houston to Port Arthur all the way to California, and we started to put pressure on these industries to clean up their act.

Céline Gounder: And he even hired a pro-bono lawyer to legally fight them. So they sued most of the refineries and plants in town under the Clean Air Act. And the industry responded. They’ve lowered emissions, put in more safety measures and are even economically revitalizing the city by buying up old buildings and rehabbing them.

Kelley’s also won a lot of big fights in town such as in 2006 when Motiva announced it would expand its Port Arthur facility – Kelley got the company to install high-quality equipment to reduce harmful emissions, health coverage for West Side residents for three years and a $3.5 million dollar fund to help entrepreneurs launch new businesses in the community.

That same year, he also blocked a chemical waste plant from importing 20,000 tons of toxins from Mexico to be incinerated in town.

And he’s still fighting the fight today:

Archival Tape of Hilton Kelley: “Here we are in the city of Port Arthur, we are taking it. Just a few years ago they tried to bring in VX Nerve Gas waste, then they tried to bring in PCB from Mexico, now they are trying to bring chemical weapon waste from Syria. How much is too much for one community?”

Céline Gounder: But Kelley knows – closing these refineries and plants is never an option.

Hilton Kelley: So we have to learn to co-exist. I mean, we love our community. We love the culture and we don’t want to really dismantle it. And that’s one reason why I stay in, and I fight so hard to push for emission reduction because closing those facilities down, it’s not going to happen. The workers want them there. Even though we want clean air. We want clean water. It’s just a catch 22. Uh, the federal government wants them there. The state wants them there. And I can’t imagine pushing to close those industries down and watching the citizens here lose everything they worked so hard for.

Céline Gounder: Kelley isn’t giving up, though. He’s in it for the long haul. Because it’s more than fighting for environmental justice. It’s the fight for his community, his family, his home.

Even though Kelley left Hollywood to take on the oil and gas industries – he hasn’t forgotten about his artistic spirit. He continues to combine his activism and creativity – through poetry. Such as in this poem called “My Toxic Reality.”

Hilton Kelley: “I see your smoke rising in the air. Two/three in the morning when you think no one is there. In the still of the night my child starts to sneeze; in the still of the night, the other starts to wheeze. Your bright, bright torch, it burns all night. To find my way through the house. I don’t even need a light.

The roar of your flame, I’ve learned to ignore, even though it’s combustion vibrating my feet up on the floor. I know I live at the back end of town and I should just be quiet and not make a sound. You might even find this a little profound, but me and my neighbors are light and dark shade of brown. I hope I’ll leave this. Don’t conspire to circumvent because these findings I have have a Sulfur, Benzene scent, excuse me, while I cough – my throat has a slight tickle. The air I breathe smells and sometimes very fickle.

If you went to take a bath and saw a rash upon your chest, would you shrug your shoulders and wish yourself the best? Because this money they give is great, and this is only flesh. But if you had the right insurance, you could go and take a test or I’m scared I’d lose my job if the pollution I attest. But if you died tonight, would your killers confess to the poison they put inside you that laid you down to rest? Would your family have to fight to pay your doctor bills as you laid six foot under upon a grassy Hill?

Now your job has gone and your company grievance has faded. Your spouse and kids tried to collect from them, but they said your death was not job related. My toxic reality, my toxic reality, my toxic reality.”

Céline Gounder: American Diagnosis was brought to you by Just Human Productions. We are funded in part by listeners like you. We are powered and distributed by Simplecast. Today’s episode was produced by Zach Dyer, Paige Sutherland and me. Special thanks to Walker Wooding for his help reporting this story.

Our theme music by Alan Vest. Additional music by the Blue Dot Sessions. If you enjoy the show please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show.

We love providing this and our other podcast to the public for free BUT producing a podcast costs money. We’ve got to pay our staff. So please make a donation to help us keep this going. Just Human Productions is a 501-c3 non-profit organization so your donations to support our podcast are tax deductible. Go to American Diagnosis dot f-m to make a donation.

And Just Human Productions is now on Instagram – check us out at Just Human Productions to learn more about the characters and big ideas we cover on American Diagnosis and our sister podcast Epidemic.

I’m Dr. Celine Gounder – thanks for listening to American Diagnosis.