S1E37: Seeking Sanctuary / Julie Levey, Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove, Pastor Jamal Bryant

“I don’t have any plans on returning in the immediate future. I don’t want history to record that COVID grew in America because of irresponsible religious groups… I want to make sure that we are good stewards of health and responsibility.” – Dr. Jamal Bryant

COVID has closed down many religious spaces, profoundly impacting faith communities. Many rituals have been disrupted, and social distancing guidelines are preventing people from gathering. In today’s episode, we hear from Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove, senior rabbi of Park Avenue Synagogue, and Pastor Jamal Bryant of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church. Together, they’ll be examining a question people of all religions are asking right now: what does it mean to be a member of a faith community during a time of social distancing?

This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Celine Gounder: I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. And this is Epidemic. Today is Tuesday, July 21st.

Before the pandemic, Friday night was something Julie Levey always looked forward to.

Julie Levey: Kabbalat Shabbat at Park Avenue Synagogue on Friday night is a beautiful service. The cantors are singing alongside a band and the space is full of families who have come together at the end of the week to be with each other and to welcome in Shabbat.

Celine Gounder: Julie is one of our interns. She’s going to be a freshman at Princeton University in the fall.

Julie Levey: We have seats in the sanctuary that are our go-to seats, so usually in the middle of the winter my family of six will be surrounded by our winter jackets piled up on the seats next to us with the prayer books all around us, and it’s just this beautiful moment where all of us come together after a week of activities and school and work when we may not have seen each other as much as we would have wanted to.

Celine Gounder: But with the quarantine… Julie and her family couldn’t experience that same sense of community… at least not in person.

Julie Levey: And as I’ve thought about my identity in the past few months, as we’ve been in this time of social distancing, this idea of community has been so much more on my mind than ever before, because the thing that we are lacking right now is community as we’ve ever known it before. And this is that this is not just about Judaism. This is about all faiths, all identities, all groups of people. We’re unable to form community in the same ways that we are used to forming it.

Celine Gounder: So in this final episode in our series with the Just Human Productions interns, we’re going to present a condensed version of Julie’s conversations with two faith leaders. One is the leader of her synagogue…

Elliot Cosgrove: My name is Elliot Cosgrove. I am the senior rabbi of Park Avenue Synagogue, which is a large conservative synagogue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

Celine Gounder: And the other is from another house of worship…

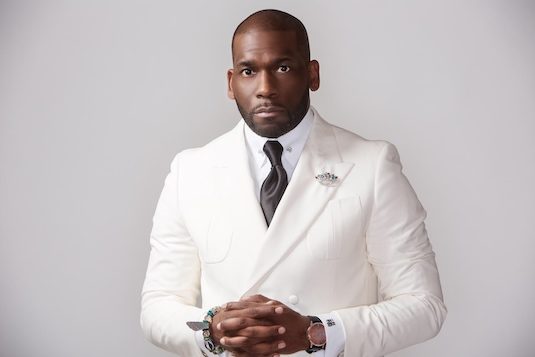

Jamal Bryant: Pastor Jamal Bryant of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church in Stonecrest, Georgia, which is metropolitan Atlanta.

Celine Gounder: Together, they’ll be examining a question people of all religions are asking right now: what does it mean to be a member of a faith community during a time of social distancing?

Julie Levey: Rabbi Cosgrove, it’s great to have you here.

Elliot Cosgrove: Thank you and I’m honored to be part of this conversation.

Julie Levey: Dr. Bryant, thank you so much for taking the time to join us. We’re really looking forward to speaking with you.

Jamal Bryant: It’s my pleasure, thank you for having me.

Julie Levey: I became aware of COVID in two different ways. I remember at the lunch table at school, my friend would joke “oh, what if college campuses are closed down,” and we would all laugh because at that point it didn’t seem like something that could ever happen. And then in late February and March, I think I became aware of how it would affect me as a senior in high school, and at the same time, another part of my brain was focusing in on how this was going to affect me and my Jewish identity.

Dr. Bryant, I’m wondering, when, when did you and your community become aware of the coronavirus and what a big deal it was going to be? What was going through your mind at the time?

Jamal Bryant: In March, it was either the first or the second Sunday was slated to be my one-year anniversary as pastor of the church. But I knew that trouble was on the horizon. And we had, as we suppose, were postponing, the anniversary cause we thought we’d be out for two to four weeks. When it became more bleak and grim, the reality just was dizzying because we thought it was just a bad rumor. An internet hoax. Or something abroad. We didn’t think it would not just knock on our door, but kick the door down.

Elliot Cosgrove: For me, there is a celebration in early spring called Purim, and we were panicked. We were panicked. We did not know whether or not we could safely bring people into the community. And so in those first couple weeks of March, that was the moment that we were facing the unknown for the first time.

Julie Levey: It’s interesting that you say that because in my mind as I think about when I first became aware of the coronavirus, Purim is what comes to mind as well because I was actually in the Purim spiel, the Purim musical, this year and I remember that as being the last time that most of the congregation was able to gather together in the sanctuary and that we were able to celebrate a Jewish holiday in person. And it was kind of funny because on Purim people wear masks, people dress up and little did we know that just a few weeks later, we were going to be wearing masks for an entirely different reason.

Elliot Cosgrove: What I discovered in my community is that people in this time of uncertainty need more, not less, ritual in their lives. A new parent, not terribly religious, their child was born during this time and they wanted to be able to bless their child with the traditional Friday night blessing at the Sabbath table and they called me and said “Rabbi, can we spend an hour on the phone and just teach me how to say that blessing.” So I have many stories like that, Julie, of people leaning in to faith during this time.

Julie Levey: Just thinking about how I’ve been feeling these past three months, I do agree that the importance of rituals and traditions has definitely increased in how I think about my connection to Judaism. And one extra weekly ritual that my family and many other families have been partaking in is Havdalah, which is a ritual that marks the separation between the end of Shabbat and the rest of the week. It’s given me perspective and helped me separate the different parts of the week and to make sure that this period of social distancing doesn’t just feel like one endless occasion. Rather, it feels like I’m still, I’m still living my life and my life is still separated into pieces that I can grasp, and that I can, I can reflect on one by one.

If I’m not mistaken. Dr. Bryant is your, is your community 12,000 families? 12,000 people?

Jamal Bryant: Yes. 12,000 families.

Julie Levey: How as the pastor of this huge community have you been able to give each member the individual attention that he or she or they may need during this time when everyone is already so far apart?

Jamal Bryant: My responsibility is to impart, equip and to develop my team and staff so that they had to make sure that everybody is administered to. What we’ve done on the other side of COVID is making sure that we are high tech and high touch. So we do zoom groups for seniors, zoom groups for high schoolers, middle schoolers, singles, entrepreneurs, so people are really finding God in intimate ways without the construct of church. They are finding how do I worship Him and not be in the sanctuary. We have been forced into mindfulness and meditation and alone time, not as a punishment. And so I think this is a great opportunity for a faith organization to really be able to stretch itself in new and profound ways.

Julie Levey: You mentioned this word sanctuary and the idea of what it means to be in a sanctuary versus what it means to create a religious space for yourself away from a sanctuary. And it reminds me of this song that we sing at synagogue sometimes, and the lyrics are, “Oh, God prepare me to be a sanctuary, pure and Holy, tried and true.” And I’m reminded of this because the song isn’t classifying a sanctuary as any physical space, but rather saying that each individual person can be a sanctuary. And I’m wondering how we can, how we can create holy spaces within ourselves when it really is impossible to be in the physical, the physical churches, synagogues, mosques, any other religious space that we might think of as that physical sanctuary that we know.

Jamal Bryant: A lot of people in the faith community are battling depression, worry, stress, anxiety, mental health challenges, because the sanctuary, regrettably, has only taught fellowship and not taught us how to maximize aloneness with God. And so I think that this is really forcing us to disconnect our, to unplug and to really focus. And I think this is really going to beat the maturing of believers when we get on the other side of this. I think that it’s going to be healing in many regards, but I think it’s going to be scarring in others, because they are those who are literally trapped at home. What do we do for the skyrocketing numbers of those who are victimized by domestic violence, as those calls have gone up 300% in COVID-19? And so for other people being at home is not a safe place. And the church is going to have to really do its due diligence of authentic ministry to give address to those needs.

Julie Levey: I wouldn’t want to forget to acknowledge how New Birth has offered a lot of free COVID-19 testing. And I’m wondering if you could share a little bit about this service that your church has been offering and why you think it’s important that New Birth is on, on the front of offering testing.

Jamal Bryant: The data is undeniable that African Americans are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. And I thought it was our responsibility and being a holistic ministry to make sure we do that. Every time we do it, it’s an average of two to 3000 that show up. We’re doing that, but I also must mention that we’re giving groceries to 8,000 families a week because the church is just not entrusted with the soul, but the body and the mind. And as a consequence, it is our endeavor to make sure that we are doing that in every possible conceivable way.

Julie Levey: As the situation surrounding coronavirus got worse and worse, the holiday of Passover, which is a very important Jewish holiday, and one that I always look forward to, was quickly approaching. So my mind completely shifted into Passover mode and into thinking, what is it going to look like now? So I decided to organize a virtual Seder. I thought, you know, maybe I would have 15 people, 15 family members there. 80 people ended up showing up and it was this first moment during a time of social distancing, where I finally felt full. I finally felt like the Jewish community that I’d been missing so much the past few weeks was together and it was a moment where I just felt like my faith was living on despite what was happening in the world around us. And not only did that give each of us a sense of purpose, but it also brought us together in a very unique way. And a sense of purpose in my mind can also translate in this time to creating a sense of hope. And I think that hope, hope is a very Jewish thing. Of course, communities around the world relate to this idea of hope, but it appears in the liturgy and it appears in texts and in stories. And if I can do just a little part in creating a little more hope from a Jewish perspective, I feel more fulfilled.

Dr. Bryant, what does hope mean for you right now?

Jamal Bryant: Hope is the expectation that we’re going to get back into the sanctuary yet not knowing when. Hope is knowing that there have been scores who have died, but many more who have survived. So we’re not sure where this is going to land or how it’ll come to a screeching halt, but I’ve got to hope that it will.

Julie Levey: For me, hope comes in tandem with history. I’ve been turning to the past to find the sense of hope and at the same time to find, to find a reassurance that, as a society or as a religion, we are equipped with the skills and with the faith and with the courage to, to face what’s in front of us.

But, Rabbi Cosgrove, as a person of faith, it’s easy to wonder why did this happen. I have this strong belief in something big, something greater, and yet, there is so much that’s happening in this world that is beyond my comprehension. We have a global pandemic. We have this other pandemic of racism which is perpetuating through our society and all of these terrible acts happening on a daily basis. It’s easy to find yourself thinking, and I know I’m finding myself thinking, why, why did this happen?

Elliot Cosgrove: I think God’s got a lot of explaining to do. Nevermind the events of the last couple of weeks with, not just the virus of COVID, but the virus of systemic racism. I think we’re all asking profound and deep and unsettling questions about our own faith, our own relationship to God, as well as our relationships to our respective communities, whatever they may be, religious, ethnic, racial, or otherwise.

Jamal Bryant: This is counter to everything that we know as faith practitioners that comes with signs and wonders. And so they were saying with COVID, that you’d have no evidence that you have it, that wouldn’t be necessarily red eyes or blemishes of the skin. And so we didn’t even have a biblical model of being healed of something you can’t see or experience. And so this really stretched faith at a capacity that we didn’t have an example to really cross-pollinate with.

Julie Levey: I’ve been feeling, you know, similar things regarding the Jewish religion, where there’s so many examples of disease in the Torah and how that’s dealt with, but all of the diseases seem to have these physical manifestations that are easy to pinpoint and easy to identify in a way that coronavirus is not. And I’m wondering, because this idea of the unknown and how scary that can be has kind of infiltrated everyone’s lives in the past few months, has your own outlook on religion or your relationship to God changed because of how you’re dealing with this idea of the unknown?

Jamal Bryant: It is exciting for me because it is making us really sharpen our concept of faith. We have westernized faith too. I want a new job. I want a scholarship. I want to be married, but now we really have to take the word at its worth. Faith is the substance of things hoped for, it’s the evidence of things not seen.

Elliot Cosgrove: Right, in the book of Job, when great affliction befalls job and one after the other, after the next, his friends offer explanations of why evil has befallen him. And then at the very end, the answer God gives is it’s none of your business, you weren’t there when the earth was founded, you weren’t there at the very beginning, there are certain things that are, that are beyond the scope of human comprehension. So, I’m working on it. Julie, I’m working on it privately. I’m working on it publicly. I have had moments in these last months that have truly challenged me faith, that I have cried alongside congregants, that I have cried at the world. And the challenge is how to praise God each and every day. And also be grateful for the world we live in each and every day.

Julie Levey: I’ve kind of come to this internal understanding that religion is not, and can’t be a safety net that can protect us from, from all bad things, from everything that’s wrong with society and from our world. But rather I view religion as a mindset through which we can begin to understand how to comprehend and approach the sorrows and everything bad that’s happening that we have no explanation for. And at least for me when I pray, it’s not a call to, you know, stop, stop the coronavirus because I understand that religion’s not going to make that happen. It’s science that’s going to make that happen. But rather prayer is a call that can give us each the strength that we need to accept the situations that we’re dealing with, heal from them and do our part to help to make them better.

Elliot Cosgrove: Right, we can’t control the slings and arrows of this world. We can control, for the most part, our response. And I think for me, in the face of evil, the challenge is not explaining God. The challenge is trying to shape the human response.

Julie Levey: Dr. Bryant, the reopening of religious spaces has been a very hot topic recently. And of course the larger the community, the harder it is to reopen. And I’m wondering what is your perspective on the reopening of religious spaces and how has the size of your congregation influenced that?

Jamal Bryant: I don’t have any plans on returning in the immediate future. We have been effective in a virtual space and plan on maintaining it. I don’t want history to record that COVID grew in America because of irresponsible religious groups. I want to make sure that we are good stewards of health and responsibility. It is a shedding light of what is already there.

Elliot Cosgrove: For a million reasons, Julie, I cannot wait for the day that you and I are together in the synagogue with the community. But look it’s a little, it’s a lot too early to talk about the light at the end of the tunnel. We as an institution, as I’m sure all forwardly looking institutions are both working on just to get to the next day but also to imagine that future world.

Jamal Bryant: So many stories on articles and blogs are about churches going in prematurely. People at risk from going to church. I want to go on record as a pastor to say please, as much as you can stay home, wear your mask, wash your hands. Be responsible and find the glory of solitude to have an opportunity for you to have a close encounter of the divine kind, for God to be able to have your undivided attention.

Julie Levey: Dr. Bryant, thank you so much for sharing, for sharing those words. I want to take your advice to heart and to be comfortable with sitting in solitude and with sitting in silence. It was so amazing to be able to speak with you today, and I really, really appreciate you giving us your time to have this conversation.

Jamal Bryant: Oh no, it was my privilege. Thank you for having me.

Julie Levey: Rabbi Cosgrove, as we wrap up, I’m wondering, I’m wondering one last question that I’m sure you’ve probably heard from other people, but my question is how do I continue to build faith and to build my relationship with a community during this time and not let this period of social distancing create barriers between myself and my religion and myself and my community?

Elliot Cosgrove: I think that this is a moment that we are all being challenged in a terrible way. And I think that we can’t control what’s thrown at us, but I think you got to lean in. I know it’s easier said than done. Not you personally, Julie, you personally, but also anyone who is asking of themselves those questions of what does community mean? What does faith mean? It’s good to ask those questions. It’s even better to lean in and get involved, and doing, doing things in our personal and in our public spheres.

Julie Levey: And I’m going to try my best to keep leaning in, to keep making those connections, to keep speaking to family members and meeting new community members. And hopefully just to, to maintain connections during this time. It was amazing to be able to talk to you. And I so appreciate your honesty, the wisdom that you shared with me and with the audience. And I am so excited to continue to be involved with the community and hopefully sometime soon to be able to re-enter our beautiful synagogue building.

Celine Gounder: “Epidemic” is brought to you by Just Human Productions. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Today’s show was produced by Zach Dyer, Danielle Elliot, and me. Our music is by the Blue Dot Sessions. Additional music care of Park Avenue Synagogue Cantors Azi Schwartz and Rachel Brook and Cantorial Fellow Josh Rosenberg. Our interns are Sonya Bharadwa, Annabel Chen, and Julie Levey.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

You can learn more about this podcast, how to engage with us on social media, and how to support the podcast at epidemic.fm. That’s epidemic.fm. Just Human Productions is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, so your donations to support our podcasts are tax-deductible. Go to epidemic.fm to make a donation. We release “Epidemic” twice a week on Tuesdays and Fridays. But producing a podcast costs money… we’ve got to pay our staff! So please make a donation to help us keep this going.

And check out our sister podcast “American Diagnosis.” You can find it wherever you listen to podcasts or at americandiagnosis.fm. On “American Diagnosis,” we cover some of the biggest public health challenges affecting the nation today. In Season 1, we covered youth and mental health; in season 2, the opioid overdose crisis; and in season 3, gun violence in America.

I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”