S4E3: Abandoned Mines, Abandoned Health – Part I / Amber Crotty, Linda Evers, Phil Harrison, Larry King, Judy Pasternak, Edith Hood, Cipriano Lucero

On the morning of July 16, 1979, a dam broke at a uranium mine near Church Rock, New Mexico, releasing 1,100 tons of radioactive waste and pouring 94 million gallons of contaminated water into the Rio Puerco. Toxic substances flowed downstream for nearly 100 miles, according to a report to a congressional committee that year.

In the 1970s, uranium mining was a good source of income, leading many Indigenous people and other locals to seek out jobs in the mines and the mills where uranium ore was processed in preparation for making fuel. The work was often grueling, but many young people didn’t have other options to support their families.

Episode 3 is an exploration of the forces that brought uranium mining to the Navajo Nation, the harmful consequences, and the fight for compensation that continues today. It is the first in a two-episode arc of reporting about uranium mining.

Working in the mills, people were exposed to a powdery radioactive substance, called yellowcake, that is produced as part of the uranium milling process.

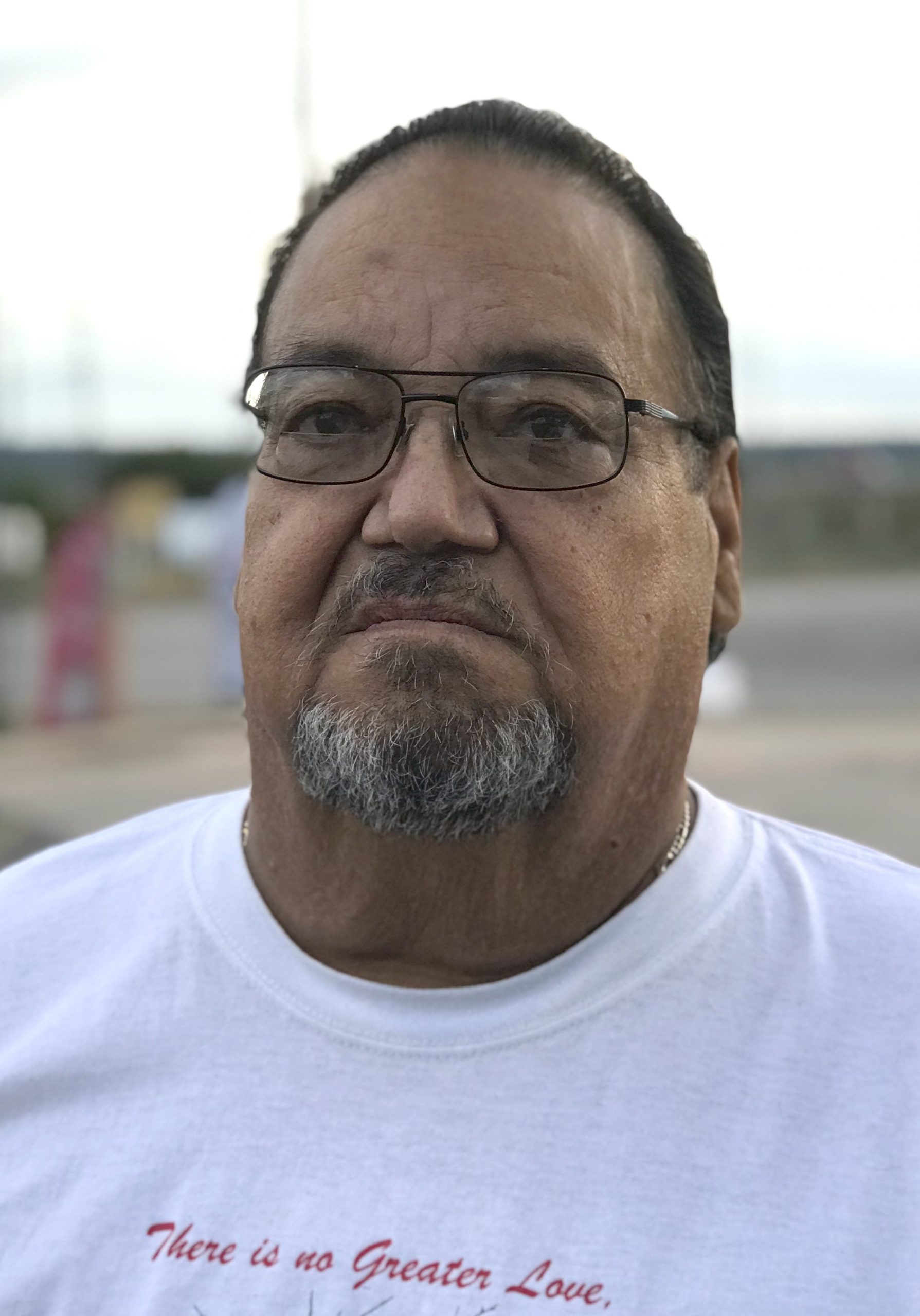

Larry King, who is Diné and a former uranium worker, said he worked in his street clothes.

“So it was just usually one of my old shirts, my pants. No gloves. No respirator. Nothing. So everybody’s breathing all that dust.”

Another former uranium worker, Linda Evers, said she wasn’t told about the dangers associated with uranium exposure.

“When we had safety meetings, it was about regular first aid,” she said. “There was no mention of radiation — or any of the side effects from it.”

The consequences of radiation exposure can build quietly in the body, over decades and generations. It can cause multiple types of cancer, birth defects, and other ailments.

–

Season 4 of “American Diagnosis” is a co-production of KHN and Just Human Productions.

Our Editorial Advisory Board includes Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, Alastair Bitsóí, and Bryan Pollard.

To hear all KHN podcasts, click here.

Listen and follow “American Diagnosis” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, or Stitcher.

American Diagnosis Podcast

Season 4 Episode 3: Abandoned Mines, Abandoned Health

Air date: February 15th, 2022

Editor’s Note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of American Diagnosis, which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

TRANSCRIPT

Céline Gounder: On March 28, 1979, Americans woke up to disturbing news.

Archival News Clip of Walter Cronkite: The government officials said that a breakdown in an atomic power plant in Pennsylvania today is probably the worst nuclear reactor accident to date.

Céline Gounder: The story made national and international headlines, including this broadcast from CBS News.

Archival CBS News Clip: The people of Middletown, Pennsylvania, lived in fear of an enemy they couldn’t see, hear, or feel.

Céline Gounder: Early that morning, a cascading series of failures happened at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. Workers at the plant lost control of the coolant systems. One of the reactors overheated, causing a partial meltdown.

Archival News Clip of Walter Cronkite: Nuclear safety group said the radiation inside the plant is at eight times the deadly level. So strong that after passing through a 3-foot-thick concrete wall, it can be measured a mile away.

Céline Gounder: By the end of the week, more than 140,000 nearby residents left their homes. Luckily, no one was killed. The accident was all over the news. Even President Jimmy Carter visited the plant for a briefing on the accident days later. Then, just a few months later, in July 1979, another accident released three times the amount of radioactive material as Three Mile Island. That time, the news barely covered it at all.

It happened at a mine in Church Rock, New Mexico — a small town on the Navajo Nation. A Diné uranium mine worker named Larry King was there that day.

Larry King: That morning, I got there at 5, went underground before 6. And when the day shift came on at 8, that’s when I started hearing people talking among themselves.

Céline Gounder: Larry grew up on the Navajo Nation in a small community called Red Water Pond Road. United Nuclear Corporation was the parent company for the mine there. Larry started working for UNC right out of high school.

Larry King: So I was only 17 or 18 years old. So four years later, this happened

Céline Gounder: There was a pond near the Northeast Church Rock mine where Larry worked. But he says it wasn’t someplace you’d want to swim or fish. It was a tailings pond. He says that’s where the wastewater and byproducts of the uranium ore extraction were held.

But that morning, he says, workers were worried.

Larry King: They were saying, “Did you see? Did you see the dam? Did you see the mill site? Did you see that huge crack?”

Céline Gounder: Larry said he had seen the same cracks up close just a few weeks before.

Larry King: And those cracks were wide enough to where my hand would fit in there.

Céline Gounder: According to an Army Corps of Engineers’ report, United Nuclear Corporation did not report the cracks to state regulators when they first started appearing.

Larry King: And so that particular morning — or the afternoon when I was going home — I looked over there. And it’s in the same location where the dam had broke.

Archival ABC News Clip: This dam cracked early on the morning of July 16. Eleven hundred tons of radioactive waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive water and acid poured through and contaminated the Rio Puerco river nearby.

Céline Gounder: That report was from ABC News. It was one of the few news broadcasts about the spill at the time.

The Diné living in New Mexico rely on the Puerco River for drinking water, irrigation, and their livestock. But now, suddenly, there were 94 million gallons of toxic wastewater in it.

Larry King: The acidity of that wastewater was equal and above the acidity of battery acid.

Céline Gounder: And these toxins didn’t just stay in Church Rock. They flowed downstream for nearly 100 miles, according to a report to a congressional committee that year.

Larry King: That Puerco wash runs through the city of Gallup, right downtown. It continues into Arizona, into Sanders, Arizona; Holbrook, Arizona.

Céline Gounder: The cleanup was slow. An official from UNC, the parent company of the mill, told a House committee that because of rough terrain, it had to be done by hand. During that same hearing, an environmental analyst noted that UNC initially assigned 10 men to the cleanup. The analyst said the workers were given only shovels and 55-gallon barrels to remove the contaminated sediment from the Puerco river.

Larry King: And all I can remember was seeing the laborers, in wetsuits, shoveling all that slime off of the embankments of the wash and scooping them into containers.

Céline Gounder: ABC News reported that some of those containers weren’t disposed of properly.

Archival ABC News Clip: We found radioactive sand shoveled into barrels and left there for the barrels to be tipped over by a rainstorm.

Céline Gounder: Residents were furious. The same ABC News report from 1979 captured the frustration at a tribal council meeting:

Archival ABC News Clip: This spill is equal to, to Three Mile Island in our minds. If it happened in Phoenix or Los Angeles, you better believe there’d be a lot of action done.

Céline Gounder: In 2007, a researcher told a congressional committee the Church Rock spill was the single largest accidental release of radioactive material in the history of the United States.

The Three Mile Island accident cleanup was completed in 1993. To this day, the Church Rock mill site hasn’t been fully remediated. Larry thinks he knows why:

Larry King: Because we’re an Indigenous community. We’re a poor community.

Céline Gounder: If you’ve never heard of the Church Rock spill, you’re not alone. I had never heard of it either, not until I started working at Gallup Indian Medical Center in 2017.

I’d reached out to some community groups while I was there. I wanted to learn more about the Diné people. They invited me to join the residents of the Red Water Pond Road Community for a yearly event commemorating the spill.

I walked with them through the area. It’s beautiful. Native grasses and sagebrush carpet the landscape. Sandy-colored bluffs rise to meet wide open skies. But a closer look reveals something else. Metal fences with signs that read, “Danger: Radioactive, Keep Out.” There are few trees. They told me the trees were chopped down so the contaminated soils under them could be removed.

Standing on Larry’s porch, I imagined the Church Rock spill running through his family’s land. I couldn’t believe that Larry — who was a young man when the spill first happened — was still fighting all these decades later for someone to put things back as they were, to clean up the radioactive waste in his own backyard.

In this episode, we’ll look back on how uranium mining came to the Navajo Nation.

Amber Crotty: It’s almost impossible to believe that any of these decisions were made for the best interest of the Navajo Nation and her people.

Céline Gounder: What, if anything, was done to protect the workers and the residents from the dangers of these mines before the Church Rock spill?

Linda Evers: We had to supply our own gloves, any kind of facial protection, any kind of hearing protection. They led us to believe that there was nothing to worry about.

Céline Gounder: And how the community fought back.

Phil Harrison: We’re losing all these boys that work in the mine. Something’s gotta be done. Let’s get an attorney.

Céline Gounder: I’m Dr. Céline Gounder, and this is American Diagnosis.

[Theme music fades out]

Céline Gounder: For the Diné, land is much more than a place. Former UNC mine worker, Larry King, says the land is literally part of his people.

Larry King: When the baby is born and the umbilical cord falls off, it’s buried in the sheep corral. And that’s how you’re tied to the land.

Céline Gounder: This connection to the land keeps people near the place where they were born. Generation after generation.

Larry King: The kids would just build their house next door. Or, either, some families in a house — they’d have about three families inside the house — and so with the Red Water Pond, there’s about four, five, six generations right there. And in my area here, my dad — this is my dad’s grazing area here. So my fraternal relatives are around me and we’re staying here.

Céline Gounder: During the 1860s, the U.S. military forcibly removed the Diné from their land. Thousands died in what became known as the Long Walk.

The Diné are one of only a few tribes who successfully negotiated to get their ancestral land back. Once they returned, they wanted to stay.

But over the next 100 years, making a living on the Navajo Nation became increasingly difficult, and eventually would make working in uranium mines look very attractive. But before we can talk about mining, we need to start with what used to be the most important part of the Navajo economy.

[sound of sheep bleating]

Sheep.

Amber Crotty: The Navajo economy was truly based on our livestock.

Céline Gounder: That’s Amber Crotty.

Amber Crotty: Our sheep predominantly provided the majority of necessities that we needed. The meat, the wool — the flock itself gave you the wealth.

Céline Gounder: Amber is a Navajo Nation government official. She grew up north of Gallup, New Mexico. These animals, she says, offered more than just economic value for her people.

Amber Crotty: There’s a spiritual connection. We have songs, we have prayers. They provide us basically everything that we need to survive.

Céline Gounder: But she explains that around the 1930s, this way of life was starting to get the attention of the U.S. federal government. And not in a good way.

Amber Crotty: They claimed not only was there overgrazing, but that overgrazing was causing a buildup of silt in the Hoover Dam. And so these are huge economic conductors, right? The Hoover Dam providing electricity, damming up Colorado river. So you have access to power, access to water. And this is how the West was created.

Céline Gounder: So the U.S. government decided to reduce the livestock population.

Amber Crotty: And when I say reduce, I mean, there’s accounts where they would come in and systematically shoot, on sight, sheep. Hundreds of sheep.

Céline Gounder: Many Diné refer to this mandated slaughtering as “the Second Long Walk.”

Amber Crotty: They simply came in, killed the livestock. There was no time — or not enough time — to butcher, to cure the meat, to secure the pelts. There literally were livestock in heaps, rotting away, on their home sites.

Céline Gounder: The tribe’s livelihood was decimated.

Amber Crotty: And so what that did was it forced the Navajo people — particularly, the men — to go out and seek jobs. And since there was really no economy on Navajo, they then looked for jobs through federal policies. Looked for jobs like on the railroad.

Céline Gounder: And … in uranium mines.

Judy Pasternak is a journalist formerly with the LA Times. She covered the issue of uranium mining on Navajo land. And she wrote the book Yellow Dirt: A Poisoned Land and the Betrayal of the Navajos.

Judy Pasternak: So, the U.S. government was aggressively seeking domestic deposits of uranium because it was secretly trying to develop the atomic bomb.

Céline Gounder: One of the key ingredients needed for an atomic bomb … is uranium. And it wasn’t easy to find, at least not in the United States. But the U.S. government found a way.

Judy Pasternak: They discovered that in the Four Corners area, both inside and outside the Navajo reservation, they could find what they sought.

Céline Gounder: This uranium suddenly became a national security asset.

Judy Pasternak: So, obviously in the beginning, it was to try to win World War II. And then afterward, of course, it was the Cold War. And there was real fear — real, real fear — that the world could end. And they thought that deterrence was going to be the only way to keep that from happening.

Céline Gounder: So the U.S. government set out to build the biggest nuclear arsenal it could muster. These uranium deposits in and around the Navajo Nation were a key part of that plan. And the federal government had a way to fast track the approvals for these uranium mines.

Judy Pasternak: The Bureau of Indian Affairs is the guardian for the Navajos and for all Indian tribes. And so the Bureau of Indian Affairs approved this on behalf of the tribe. There is a tribal council. They knew what was going on. They also really liked the idea of having jobs and did not understand the danger involved.

Céline Gounder: Amber Crotty agrees. The council needed more jobs. Leaders thought the mines would bring in more revenue for the Nation. But they weren’t the ones really pulling the strings for these mining contracts.

Amber Crotty: The federal government was our trustee. They literally were in our council chambers where we make decisions and make laws. They were the attorneys, they were the superintendents, and they basically made a majority of the decisions on behalf of the Navajo Nation people. And so they played a critical role in the decision-making during that era, during that period. It’s almost impossible to believe that any of these decisions were made in the best interest of the Navajo Nation and her people.

Céline Gounder: Since uranium mining was being driven by war efforts, working for the mines was being messaged by the government as patriotic.

Judy Pasternak: Not realizing that even if it’s not in a bomb, it can pose a danger. But this was a silent danger. And it was an invisible danger. And it was a long-term danger.

Céline Gounder: So the uranium mining companies flooded in.

When we return, we’ll hear how the invisible danger of uranium mining affected workers and their families. That’s after the break.

[MIDROLL]

Céline Gounder: Edith Hood remembers the arrival of uranium companies as a kid.

Edith Hood: I don’t remember how old I was, but this was the 1960s. That’s when exploratory drillers came in.

Céline Gounder: Edith is Diné and grew up on the Navajo Nation not far from Church Rock. She’s from the Red Water Pond Community, the same place where Larry King grew up.

Edith Hood: We did not know why they were here, but they started drilling here and there, just randomly. There was traffic. Noise. And all that noise [sighs] was big machineries.

Céline Gounder: Edith didn’t like the noise or dust of the mines when she was a kid. But when she grew up, she took a job working for Kerr-McGee, one of the uranium mining companies in the area.

Edith Hood: I worked as a probe technician.

Céline Gounder: Edith worked 2,000 feet underground. After the miners would blast away rock, it was Edith’s job to run ahead and see what they had uncovered.

Edith Hood: And so, after that, they would say, “hurry, hurry!” And so we have to go in there and measure and take samples of the ore, see if it’s reading low or if it’s reading high, if it’s worth mining.

Céline Gounder: Lots of young people found work in the uranium mines. There were risks that came with it — people were working with explosives, after all. But she says no one ever talked about the other risks that came with uranium mining.

Edith Hood: They didn’t say it was unsafe to work there or anything. We went through a safety class, but never did that come up.

Céline Gounder: Linda Evers says the same.

Linda Evers: When we had safety meetings, it was about regular first aid: How to treat a burn. If you break your leg, do this. There was no mention of radiation or any of the side effects, ever mentioned.

Céline Gounder: And Larry King.

Larry King: I was never told the hazards of working in the mines.

Céline Gounder: And Cipriano Lucero.

Cipriano Lucero: If I would have known then what I know now, I wouldn’t have even gone in there.

Céline Gounder: These mining jobs were grueling work. But many of these families didn’t have other options.

Cipriano Lucero: Well, I got married, and I needed to support my family. So I went to the Anaconda mills, started working there.

Edith Hood: I think everyone was in need of a job, especially the local people. So, anything to get money, I guess.

Linda Evers: My dad worked in the mines. My uncle moved here. He’s a hard rock miner. My step-grandfather, couple of more uncles.

Cipriano Lucero: You had to work somewhere, you know? That was one of the best jobs there was.

Linda Evers: This is where the money was at. So the whole family just kind of gravitated here.

Larry King: When I was there, just doing that dirty job, I always thought to myself, “This is not for me. I want a better job. I want a surface job. I want a clean job.”

Céline Gounder: These workers say they didn’t know about the dangers of radiation poisoning at the time. But others did. In her book Yellow Dirt, journalist Judy Pasternak reported that as early as 1949, there were government reports of the dangers of working in uranium mines.

Judy Pasternak: They knew that radon buildup, that was a byproduct from uranium, could cause lung cancer down the line. They knew that there were ways to ventilate mines, but they were expensive. They did not want to scare the workforce. That was their thinking. Because that would slow things down.

Céline Gounder: Workers say they didn’t question the lack of protective gear these mining companies gave them.

Larry King: Rubber boots. Hard hat. That was it.

Céline Gounder: Larry says he worked in his street clothes.

Larry King: So it was usually just one of my old shirts, my pants. No gloves. No respirator. So everybody breathin’ all that dust.

Céline Gounder: Working in the mills, people were exposed to a powdery yellow substance. It’s produced as part of the uranium milling process. It’s called yellowcake. Cipriano remembers it got everywhere.

Cipriano Lucero: We had a pair of white coveralls, but after we got out of there, they were covered with a powdered mustard. And then we’d take them home, and my wife would wash them with our kids clothes and our clothes. Contaminate everything. The water would come out dirty yellow.

Céline Gounder: Linda says this toxic yellowcake also came home with the miners in other ways.

Linda Evers: When dad would get home from work, we’d run to meet him at the door and whatever he didn’t eat in his lunch — cookies or apples — he’d let us have it. Nobody thought anything about it because nobody ever told us what the dangers were from working in radiation.

Céline Gounder: Linda worked in the mines, too. She started in 1976, right out of high school.

Linda Evers: One of my first jobs was to get inside the acid tanks and chip corrosion off the acid tanks. And I didn’t have any protective gear. They just told me when I started feeling lightheaded, I might want to come out and get some fresh air.

Céline Gounder: Another job she had was checking the levels of the tailings ponds. That’s where wastewater and other byproducts of uranium milling were stored. The same kind of water that spilled in the Church Rock accident.

Linda would climb into a boat and row out into the middle of the toxic water to measure its depth.

Linda Evers: One afternoon, in one of these wicked windstorms that we get out here, we were coming back from taking our measure, me and one of the crew members, and the wind caught the boat and flipped us over in the tailings pond and … we swam back to shore.

Céline Gounder: Linda was drenched. She says she walked back and told her supervisor what happened. As she remembers it, he told her to take a shower and go back to work.

Linda Evers: That was their solution for being dunked in the tailings pond. And that wasn’t just uranium. That was all the chemicals that they used in the leaching process. I have skin issues on my hands and my legs. My skin gets bubbly, and then it blisters up, and then it turns really hard and just peels off in chunks.

Céline Gounder: Linda says her duties did not change when she was pregnant.

Linda Evers: When I told them I was pregnant, they told me, “Oh, you can work until you can’t reach the belt anymore.”

Céline Gounder: Linda says she continued to work up until she gave birth.

Linda Evers: And my son was born May 12. And by July 4, he was in the hospital having surgery. ‘Cause his guts were messed up. His intestines were twisted, his stomach didn’t form right. So they had to go in on a two-month-old baby and reconstruct his guts. So he, he could eat until he was full. And then he’d just throw everything back up. He was basically starving to death.

Céline Gounder: Her first born recovered. But once he did, Linda had to go back to work. The best-paying jobs were in mining.

Linda Evers: I needed money. Now I had a baby, so I went back to work. And when I got pregnant with my second kid, they told me the same thing at a different company. “No, no, you’re OK. You can work.” Well, my daughter was born without hips.

Céline Gounder: Linda’s daughter has since had multiple reconstructive surgeries. And she’s had two hip replacements. Linda asked the doctor what he thought was going on.

Linda Evers: I mean, every mother wants to know. What was it? Was it me? Did I do something wrong? And he said, “You know, the only time I’ve ever seen this complete mass destruction on a fetus, on a baby, is when somebody has been overexposed to radiation.” Now, I don’t know if that’s the truth, but [snaps fingers] my lightbulb went off right away. I was like, “Oh my God.” So I told him what I did, and he’s like, “Yeah, you probably shouldn’t have been working there if you even planned on getting pregnant.”

Céline Gounder: Linda says she has had her own share of health issues, too. She’s had breast cancer twice. She was diagnosed with degenerative joint and bone disease. She lost all of her teeth and has had to replace joints in her knees. And, she says, the other uranium workers in her family have also experienced high rates of cancer.

Linda Evers: My uncle that was the good hard rock underground miner died 22 years ago with spine, lung, liver, pancreatic, brain, and kidney cancer.

Céline Gounder: Linda and her family aren’t alone. A survey of more than 1,000 former uranium workers reported a slew of health issues: kidney cancer, blood disorders, sterility, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, emphysema, and a variety of tumors.

Edith said she battled lymphoma. Larry said he has everything from a heart condition to high blood pressure to asthma.

The same survey found that even spouses of uranium workers, people who never worked in the mines or mills, were affected too. Forty percent of spouses reported at least one miscarriage, stillbirth, or child with a birth defect.

Health conditions from radiation exposure can take decades to show up. Cipriano says workers didn’t connect their health issues with the uranium industry until years later.

Cipriano Lucero: We didn’t find nothing else out till we got sick, a lot of us.

Céline Gounder: The uranium boom did not last. By the time of the Church Rock spill in 1979, the military was no longer the largest buyer of uranium in the U.S. — domestic power plants were.

And that created another problem. The Three Mile Island incident galvanized the anti-nuclear power movement in the U.S. Years passed before another nuclear power plant was authorized to be built. Uranium prices plummeted. And the mines started to close.

Edith, Linda, and Larry said they were all laid off. By 1982, United Nuclear Corporation closed the Church Rock mine and mill site. It never reopened. After 40 years of uranium mining, the boom had bust.

Here’s Larry King again.

Larry King: I started to understand what these mining companies were all about. They’re not permanent jobs. They just come, get what they need and go out, and leave all the waste pile for the community to deal with.

Céline Gounder: By the 1990s, there were more than 500 abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation alone, according to the EPA. In her book, journalist Judy Pasternak describes when the companies left, many never bothered to clean up after themselves. Some barely locked the gates behind them on the way out, she says.

Judy Pasternak: The mines were open. The shafts were open. People sometimes would, you know, put their sheep in there to shelter them from the winds and the rain or the winter. Kids would go play in them.

Céline Gounder: Judy reported piles of radioactive mining waste were left out in the open. No fence. No sign.

Judy Pasternak: They were like these cool mountains and in the winter, suddenly there was a place to sled, you know, and they would go in the summer and dig caves and hang out in them.

Céline Gounder: So, how come no one took care of this? Well, bankruptcy. Going bankrupt doesn’t mean a company is no longer responsible for the cost of a cleanup. But it makes it much harder for the government to track down the money to pay for it.

In 2015, a U.S. bankruptcy court determined that Kerr-McGee, the same company Edith Hood worked for, shifted billions of dollars to a subsidiary to try to avoid paying for environmental cleanup. The company was fined nearly $1 billion.

But it’s not always clear who the authorities should pursue. Many mines date back to the 1940s. Paperwork was lost. Companies went out of business.

Here’s Navajo council delegate Amber Crotty again.

Amber Crotty: Because this is in the ’50s, ’60s. And, really, my understanding from our lawyers is in the court of law, that has to be an entity that they can formally file a case against. So these orphan mines, there’s nobody to do that because it simply does not exist.

Céline Gounder: Judy also says there was a general lack of enforcement of the laws that were in place.

Judy Pasternak: I talked to one inspector who’d basically said that he felt that the mining companies have been patriots and helping the country defend itself. And he didn’t want to stop them from making a profit. And then it would cost money to fill up all those holes. And things were not so urgent after that because now we were just talking about individual Navajo lives.

Céline Gounder: The Diné are not the only Native people to encounter the problem of abandoned uranium mines and radioactive accidents.

Not long after the Church Rock spill, there was an accidental release of radioactive gas on Cherokee land. In 1986, an accident at the Sequoyah Fuels Corporation site, operated by Kerr-McGee, in eastern Oklahoma led to the death of James Harrison, a Black man of Cherokee descent who worked there, according to a review by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Abandoned uranium mines also impact the Ute Tribe in Utah, the Spokane Tribe in Washington, and many more, according to the Department of Energy.

Decades passed on the Navajo Nation. Reporter Judy Pasternak wrote that many mines and mills were not cleaned up. And then …

Judy Pasternak: All of a sudden, the men started getting sick. And so there’d be these little hamlets where there were no men because they had all died. And, finally, some of the widows were talking about it, and they realized the only thing that these guys had in common was that they had been uranium miners.

Céline Gounder: So the community banded together to do something about it. Phil Harrison, a citizen of the Navajo Nation, lost his dad to lung cancer at age 46. Harrison says he worked in the uranium mines for nearly two decades.

Phil Harrison: This whole issue was brought to a Chapter House in Red Valley. One gentleman, he said, “Ladies and gentlemen, do you know what’s happening around here? We’re losing all these boys that work in mine. Something’s gotta be done. Let’s get an attorney.” So that’s how the first grassroots organization was formed on the whole Navajo Nation. And I just happened to be there and he pointed at me and says, “Your father died; can you help?”

Céline Gounder: Phil couldn’t say no.

So the organization decided to go to the top, the very top. Phil and a few others flew to Washington and found a lawyer to help them sue the U.S. government. The trial took three weeks in 1983. The judge deliberated for a whole year.

But … they lost.

So, instead, they decided to take the issue to Congress. That fight took nearly a decade. But, finally, in 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed into law the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, also known as RECA.

Here’s former Rep. Wayne Owens of Utah on the House floor:

Archival Tape of Rep. Owens: Today we provide a formal apology and a compassionate payment to those few victims who survived and to the living heirs of those who did not.

Céline Gounder: For the first time, those who had been exposed to radiation through uranium mining or nuclear bomb testing could now be compensated for the damages.

This law passed more than 45 years after uranium mining first came to the Navajo Nation.

For many, that help came too late.

Phil Harrison: My dad knew that something was going to be done about this. But, uh, he, he died before that. He died before that.

Céline Gounder: But many uranium workers aren’t covered under RECA.

Linda Evers: Right now, the cutoff date is Dec. 31, 1971.

Céline Gounder: The Radiation Compensation Act only provided compensation to those who worked in the mines and mills before 1971.

Linda Evers: Well, the peak of uranium mining in this area was in 1979.

Céline Gounder: That means all of the uranium workers you’ve heard from so far can’t get compensation under that law.

Amber Crotty: RECA is the tip of the iceberg. What RECA provides for the miners is, maybe, the first step in the right direction.

Céline Gounder: The fight to get compensation to uranium workers is still going on today.

There are many uranium workers who won’t live to get care, compensation, or recognition. Remember Cipriano Lucero? The man who came home to his wife and children with his coveralls dusted in yellowcake? He passed away after we spoke with him.

Linda Evers: It was all about production and profit, and they willingly sacrificed us for that. So the government made their cut, the companies made their cut, and they left us hanging, and we’re still hanging.

Céline Gounder: But the Diné and other uranium workers are not giving up. In the next episode, we’ll hear from residents who conducted their own research on the impact of radiation on their community when no one else would.

Judy Pasternak: This is not just a victim story. The residents actually banded together to get radiation detectors as well. And, suddenly, the government said maybe we should be there too.

Céline Gounder: Those efforts caught the attention of some in Washington, like former Rep. Henry Waxman from California.

Hearing Tape of Henry Waxman: It’s hard to review this record and not feel ashamed. What’s happened just isn’t right. And that’s why we’re holding today’s hearing. We want to know what has to be done, who needs to do it, and what resources will be required to fix this.

Céline Gounder: That’s next time on American Diagnosis.

[Music up]

CREDITS

This season of American Diagnosis is a co-production of Kaiser Health News and Just Human Productions. Additional support provided by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and Open Society Foundations.

This episode of American Diagnosis was produced by Zach Dyer, Adreanna Rodriguez, and me. We’re funded in part by listeners like you. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

Our Editorial Advisory Board includes Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, Alastair Bitsóí, and Bryan Pollard. Taunya English is our managing editor. Oona Tempest does original illustrations for each of our episodes.

Our interns are Bryan Chen, Julie Levy, Sophie Varma, and Maji Qadri.

Our theme music is by Alan Vest. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

If you enjoy the show, please tell a friend about it today. And if you haven’t already done so, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

If you’re enjoying this show, check out Season One of the Where It Hurts podcast. It’s a story about what happens after a small-town hospital packs up and leaves. Locals lost health care. Health workers lost jobs. The hole left behind was bigger than a hospital. Where It Hurts takes you to an often-overlooked part of the country where people are making do — despite painful cracks in the health system.

Follow Just Human Productions on Twitter and Instagram to learn more about the characters and big ideas you hear on the podcast. And follow Kaiser Health News on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Subscribe to our newsletters at khn.org so you never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to American Diagnosis.

END

Guests

Cipriano Lucero

Cipriano Lucero

Larry King

Larry King

Linda Evers

Linda Evers