S2E9 / Sharing Opana & Syringes in Small Town Indiana / Carolyn Wester, Will Cooke, Wayne Crabtree

Opioid abuse is affecting small towns across the U.S. in unprecedented ways. In 2015, Austin, Indiana was ground zero for one of the biggest HIV outbreaks in U.S. history — the end result of sharing Opana and syringes.

Note: This season of American Diagnosis was originally published under the title In Sickness & In Health.

This podcast was created by Just Human Productions. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast. We’re supported, in part, by listeners like you.

Bekki: This busted my family wide open… Me and my husband, we’re college educated. We worked for a living in professional careers. … My husband has been a mailman for 25 years. We’re good people by all standards, and it happened right here, and there was nothing I could do to like… What am I going to do? Ground him, when he’s 20 years old? We threw him out. My husband threw him out, and it was in that eight weeks, is when he contracted HIV.

Celine Gounder: This is Bekki. She lives in Austin, Indiana–a small town of about 4,000 people. And in 2015, Austin was ground zero for one of the biggest HIV outbreaks in U.S. history. During the outbreak, Bekki’s son was diagnosed with HIV. He was one of about 200 people diagnosed with HIV in Austin in a single year. To put that in perspective, Austin had an HIV infection rate higher than the worst hit countries in Africa. Bekki, who worked for years at a methadone clinic providing addiction treatment services, had never seen anything like it.

Bekki: There were probably 40 of us counselors. Nobody talked about HIV anymore. It just wasn’t a thing anymore. When I first started there, I had one heroin IV user in like ’08, but by 2013, every single intake I had was an IV user.

Celine Gounder: Welcome back to “In Sickness and in Health,” a podcast about health and social justice. I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. In the past, we thought of HIV and hepatitis C as diseases of big cities like New York or San Francisco. But, in recent years, they’ve taken root in rural America. In this episode, we’re taking a look at how opioid abuse is impacting rural communities in unprecedented ways. We’ll hear about the HIV and hepatitis C outbreak in Indiana, and how public officials responded. And, we’ll look at where conditions are ripe for this to happen again, and what public health officials are doing to prevent what some are calling a “ticking time bomb.”

Will Cooke: Austin, it looks very much like you would think of a stereotypical small town, America. The downtown is basically one street called Main Street. That’s where my practice is, and several businesses, railroad track, and a gas station. That’s pretty much it downtown.

Celine Gounder: That’s Dr. Will Cooke. He’s the only doctor in Austin, Indiana. Will is guided by his Christian faith, and it’s one of the reasons he became a family doctor.

Will Cooke: I wanted to be in a community, and be able to work with an entire family or an entire community over their entire lifespan. I don’t know exactly know that I understood what that meant [laughs] back then, but it just was this drive I had, this calling that I had, that I was wanting to work with a community, over my career, to hopefully make that community a little better.

Celine Gounder: This desire brought Will to Austin.

Will Cooke: I remember when I first opened my practice in Austin, in 2004, looking around, I was just overwhelmed with how desperate people’s lives could be right in America…Thinking back to medical school, there was really nothing that I was ever exposed to throughout medical school and residency that ever prepared me for the level of desperation and need that I was seeing in people’s lives.

Celine Gounder: By all accounts, Austin is very poor. According to state figures, one in five adults in Scott County–where Austin is located–live in poverty.

Will Cooke:We have about a 65% Medicaid base in my practice, which is really high… We have a sliding fee for those without insurance. We look at people’s income, and we go by poverty guidelines and knock a bunch off their bill and go all the way down to, I think, $5…

Celine Gounder: From day one of his practice, Will realized that many of his patients were addicted to prescription pills. The three big ones? Percocet, Soma and Xanax. Will suspected that other doctors had prescribed these meds too freely and in the process, many in the community had become addicted. The small town of Austin was engulfed by addiction and its downstream effects.

Will Cooke: I knew, we needed help so I started reaching out to the health department and the county designated Mental Health Organization and others… ‘There’s something really bad going on up here in Austin and I need help. I’m the only primary care provider in this town. I’m trying to provide primary care services the best I can, but there’s this overwhelming addiction issue, a mental health issue, and I need help.’

Celine Gounder: Will tried his best to sound the alarm, but his efforts were mostly ignored by health departments and agencies. Meanwhile, drug abuse in Austin continued. Oxycontin took hold of the community, and then Opana, another potent prescription opioid, arrived on the scene.

Bekki: From what I understand, Opana was a different animal. That was where my son, got in trouble, right there, was with Opana.

Celine Gounder: That’s Bekki again. Her son first used prescription painkillers when he was 15. Bekki asked that we not use her son’s name or their last name.

Bekki: He had messed around with Percocets, actually was prescribed those because he had to have surgery on his leg when he was 15, and learned right away that he liked the way they made him feel.

Celine Gounder: Like many in town, Bekki’s son made the switch to Opana. But Opana was different from other prescription opioids. In 2012, the drug’s manufacturer, Endo Pharmaceuticals, reformulated Opana in an effort to deter abuse and to extend the company’s patent on the drug. When the new version of Opana was crushed, it turned into a gel. The idea was to make it hard to snort and hard to inject. But add a little water and heat it up? You’ve now got an injectable liquid.

Bekki: That’s the only way you could do them, was to melt those down and to use the needle. … My son used with one of his cousins, and they didn’t have any money. They could go in together, the two of them, and buy a pill for $40 then. … It was shocking to me because I had a lot of experience with opiate treatment, but this was different and it was brutal.

Celine Gounder: All this was a recipe for disaster. An opioid that had to be injected, that was potent but pricey per pill, so it made sense for a couple of people to share one dose. And Opana doesn’t last long, so users needed a few hits a day, which led to a lot of people sharing, both the Opana pills and the paraphernalia they used to inject. Around the same time, Will Cooke, the lone doctor in Austin, was picking up shifts at the local emergency department to make ends meet. A lot more patients started coming in with infections related to injection drug use.

Will Cooke: Myself and the other emergency room providers really were shocked with the increase in the number of… those infections that we were seeing in the emergency department. … We saw an increase in endocarditis and cellulitis and the like. We did not have a needle exchange at the time, and so most people were sharing needles and just using the same needle over and over and over again.

Celine Gounder: Some people bought needles and syringes at the pharmacy or even from drug dealers, but many couldn’t afford to buy their own or didn’t know how unsafe it was to reuse or share needles. And this made it easy for blood borne infections like endocarditis, when bacteria infect heart valves, and hepatitis C to spread among drug users in Austin.

Will Cooke: Scott County was third out of 92 counties for Hepatitis C cases in 2011, 2012, 2013. As you know, Hepatitis C spreads the same way as HIV. … So… people were proactively sharing needles throughout this. This was a warning sign, and we didn’t really do anything about it until it was too late.

Celine Gounder: Hepatitis C is widely considered to be a harbinger of HIV. It’s transmitted the same way as HIV, but since it’s more infectious, we tend to see it come first. Doctors know this, which is how Will knew it was only a matter of time before HIV hit Austin. In Scott County, there had only been three new HIV diagnoses in the prior ten years. But then, in February of 2015, thirty new cases of HIV were reported. Bekki couldn’t believe what she was hearing.

Bekki: Until the needle use became so predominant, honestly, HIV was the furthest thing from our minds. … We were seeing the papers talking about HIV, and I was like, “Oh, nah.” I was, of course, worried about my kid but I knew, “He’ll be okay. They’re just making a big deal.”

Celine Gounder: But, the number of new HIV infections kept going up. And Bekki urged her son to get tested.

Bekki: He’d be like, “Mom, I’m fine. I just used with my cousin.” He was in treatment, and they did all the tests, and he was fine. “If he had something, I would have it. If he’s not, then I don’t.”

Celine Gounder: Finally, her son agreed to get tested.

Bekki: I went to the bathroom when I took him there, while we were waiting on him to call me back. And, I could hear through the wall … I couldn’t hear what the nurse said, but I heard my son. He was trying to not cry. He was trying to keep a straight voice, but he said, “What am I supposed to do now?” … And, he got a positive. … I had to keep my face right. I wanted to break down but I couldn’t. I had to be strong for him. He, of course, lost it when he got away from everybody and was just in the car with me… And I said, let’s just worry about one thing at a time. I had to talk him down off the ledge. It was terrible. … It it was just the worst day in my life.

Celine Gounder: By this point, Austin had a full-blown HIV outbreak on its hands. Bekki’s family was hit hard. Not only did her son test positive for HIV, but so did her nephew and three cousins. At the peak of the outbreak, there were twenty new HIV infections in Scott County a week. Local, state and federal health officials urged Mike Pence, who was then the Governor of Indiana, to lift the state’s ban on syringe exchange programs. At the time, syringe exchange programs were still illegal in the state of Indiana. Syringe exchange programs let people trade in used syringes for new ones and are a proven way to fight the spread of infections like hepatitis C and HIV. Will, who’d previously been told that syringe exchange programs enable drug use, decided to look into the issue himself.

Will Cooke: When this happened, I started doing my own research about it and found just an incredible wealth of information. For example, that the World Health Organization had recognized the value of needle exchange decades ago. And that only in America and I think one other country was it stigmatized to where it was not accepted as appropriate care and harm reduction. …There is overwhelming evidence, that we know for a fact that when a community has access to a syringe service program, the spread of HIV and hepatitis C, endocarditis, soft tissue infections, all of those decreased. Those that enter into recovery increase. We know this is true. Ideology stands in the way of accepting that. Although the evidence is strong, Mike Pence, a hard-line conservative, was morally opposed to syringe exchange programs.

Will Cooke: To me, it’s inconsistent with our calling as Christians to not bring care to those that are hurting and in need. Over and over and over again, in the scripture it says that we’re supposed to feed the hungry, to heal the sick… If somebody’s in need, were supposed to be there for them. We’re not supposed to sit back and condemn them from afar and say, “If you would just pray harder, you would be okay.”

Celine Gounder: After immense public pressure and more than two months after the outbreak was identified, Mike Pence finally declared a public health emergency in Scott County, Indiana. He issued an emergency order allowing a syringe exchange program in Scott County initially for 30 days, and later signing this into law.

Will Cooke: When the HIV outbreak happen, all of a sudden everybody wanted to be in Austin. We had CDC there and the State Department of Health. And… sure enough, they got more funding, and they were able to come up and finally be able to provide some of those services that we needed.

Celine Gounder: The Scott County syringe exchange opened in downtown Austin at the end of March 2015. It was a one stop shop that offered users clean needles and also an array of other services like counseling, drug treatment and HIV testing. Austin also got funding to open an HIV clinic in Will Cooke’s office. When Bekki learned her son tested positive for HIV. She took him to see Will and from there, he got connected to HIV treatment services.

Bekki: And they were on it. They had infectious disease doctors there. They had people there signing them up for benefits, Medicaid to get any… like their social security cards or birth certificates they needed. They had a lot of good things going on there. … We got him on the medication. His numbers went down drastically. … He was virally suppressed. … It went from 300 and some thousand to 29 over the course of a few weeks. So he had a very good response to the medication. … They treated him so good like he was the finest citizen in Scott County. … Dr. Arno told him before we left the very first day, she said, “You’re going to die of a stroke, a car wreck, or a heart attack, just like the rest of us.”

Celine Gounder: Bekki still doesn’t know exactly how her son got HIV, but all signs point to sharing needles and syringes.

Bekki: I told him once when he was talking about his cousin. He said, “Well, I just used with,” he had his name. “so I’m not worried about it.” I said, “Yeah, but you don’t know who he uses with.”…That’s how it happens, you know what I mean?

Celine Gounder: Will, who helped bring the syringe exchange program to Austin, believes it’s been essential to stemming further spread of HIV and getting people in the community into treatment.

Will Cooke: Before the syringe service program started, we had 74% of people injecting sharing needles. Then, after the syringe service program, only 22% were sharing needles. It’s an overwhelming reduction.

Celine Gounder: When the Austin HIV outbreak was at its worst, it became a national flash point for the opioid epidemic. How could we have let it get to this point? Some communities, like Louisville, Kentucky, understood what was at stake and sprang into action almost immediately to put preventive measures in place.

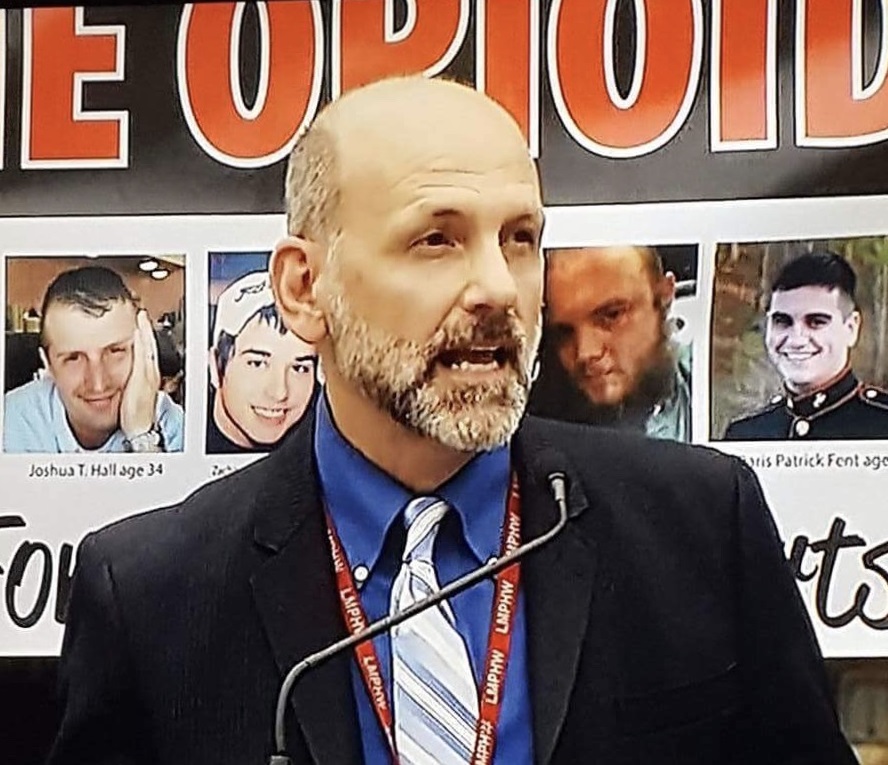

Wayne Crabtree: My name is Wayne Crabtree and I am the director of the Office of Addiction Services at Louisville Metro Public Health and Wellness and also have been a certified alcohol and drug counselor since 1995.

Celine Gounder: Wayne helped to set up a syringe exchange program in Louisville, Kentucky, which is little more than a half hour’s drive south of Austin, Indiana.

Wayne Crabtree: We know that diseases don’t stay put, and you’re not necessarily just using in Austin. You’re going to use wherever you are. … So we knew it was critical. It was absolutely critical that we get something going quickly. And so that’s what we did.

Celine Gounder: To rally support for syringe exchange programs, Wayne and his team explained how costly an HIV or hepatitis C outbreak could be to Kentucky.

Wayne Crabtree: So we basically lined out the financial. … if we do nothing… and if you have what happened in Austin, Indiana here… it would be … millions of dollars to address. … So, I think, the bipartisan support, was there as a result of that. … They got it. And they understood that this was a public health intervention to stop the spread of blood-borne diseases.

Celine Gounder: In March of 2015, Kentucky’s law allowing health departments to set up syringe exchange programs went into effect.

Wayne Crabtree: Within 10 weeks, June the 10th of 2015 we opened our syringe exchange six days a week. … That’s almost unheard of to have a public health program implemented within 10 weeks.

Celine Gounder: The syringe exchange program provides clean needles and syringes and also other services including HIV testing, naloxone in case of overdoses and substance abuse counseling, as well as referral to medical and social services.

Wayne Crabtree: … our local syringe exchange, the one that’s fixed site, is a block away from the care coordinator program so we can literally, if we test them as HIV positive, we can literally walk them over to the care coordinator program, which they take over from there and find out what what services they would be eligible for.

Celine Gounder: For Wayne, these programs are crucial to preventing further spread of HIV and hepatitis C, but they’re also about keeping people alive and safe.

Wayne Crabtree: …if we weren’t open these folks would still be injecting. They’d just be rummaging through dumpsters trying to find syringes and getting them wherever they possibly could… and then reusing multiple times, and then increasing the incidence of endocarditis and cellulitis and all that goes with that. ‘Cause it’s not just HIV and hepatitis C either. There are other things as a result of even using your syringe multiple times, not even sharing. If you use your syringe multiple times that you’re much more likely to develop endocarditis or cellulitis as a result of that.

Celine Gounder: We’ve all got bacteria on our skin. But when it gets injected into the skin by a used needle, these bacteria can cause infections in the skin, what’s called cellulitis. And when these bacteria spread through the blood, they can infect the heart, causing endocarditis.

Wayne Crabtree: So, it’s a win-win in our city. ‘Cause just treating endocarditis, the visit, is $54,000, approximately.

Celine Gounder: Wayne sees these programs as cost-effective and common sense.

Wayne Crabtree: … it’s like getting in a car and putting on your seatbelt. You know that’s not telling you to go get in an accident, it’s telling you that if you are in an accident, we’re going to save your life.

Celine Gounder: Although HIV and hepatitis C transmission has been brought under control in Austin, Indiana, health officials believe it’s a bad omen of things to come, in other parts of the country.

Carolyn Webster: …the opioid epidemic has been brewing in Tennessee for several decades… So, as a medical director for HIV and STD and viral hepatitis, my focus is obviously primarily on the prevention and identification and treatment of the downstream infectious complications of the opioid epidemic.

Celine Gounder: That’s Carolyn Webster. She works for the Tennessee Department of Health. For Carolyn, it’s not a matter of if… but when Tennessee has to contend with its own outbreak of hepatitis C and HIV.

Carolyn Webster: …all it takes is a little bit of crossover between someone who’s got HIV and there’s, you know an injection drug user, and then both of these communicable diseases can be introduced into the other environments, and we certainly see overlap already. So I think… it’s not a matter of if … but when.

Celine Gounder: After the Austin, Indiana outbreak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a nationwide study to identify counties where the next outbreak might occur. Researchers found that the communities most vulnerable were predominantly poor and white, with high unemployment rates and high rates of overdose death. Many of them were in Appalachia, including Kentucky and Tennessee.

Carolyn Webster: The HIV vulnerability assessment conducted by the CDC identified 220 counties who had a high vulnerability of experiencing an HIV, Hep C outbreak among people who inject drugs, as seen in Scott County, Indiana in 2015. And 41 of those 220 counties identified as being highly vulnerable are located in Tennessee. That 41 of Tennessee’s 95 counties, and those counties are home to about 20% of the state’s population.

Celine Gounder: In 2016, there were more than 20,000 new cases of hepatitis C in Tennessee. Although “red states” like Tennessee haven’t historically supported syringe exchange programs, it was clear they needed to take action before it was too late. In May of 2017 the state legislature green-lighted syringe exchange programs in Tennessee. By law, the syringe exchange programs are required to offer other wraparound services as well, similar to what’s offered in Austin and Louisville, like HIV testing, drug treatment and other harm reduction services. Although syringe exchange programs are now legal in Tennessee, the law states that no public funding can be used to purchase needles, syringes or other injection supplies. And their work is currently carried out by non-profits, not the department of health. Although decades of research have shown that syringe exchange programs reduce the spread of HIV and hepatitis C and save money, it can still be an uphill battle to keep them open. At the end of 2017, Madison and Lawrence counties–both in Indiana–voted to shutter their syringe exchange programs. Here’s Will.

Will Cooke: When you look at communities like Lawrence County that, unfortunately, closed the syringe service program that they had in place. It’s really, really unfortunate. It’s a place where people are putting their own ideology about the needs of the community. … Rodney Fish, with one of the commissioners in Lawrence County, when they made a vote, and he quoted second Corinthians 7:14 with a justification for why he was voting against the syringe service program. It says, “If my people who are called by my name will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” That was his justification for not needing a syringe service program.

Celine Gounder: For Will, who puts his Christianity at the center of his work, he believes syringe exchange programs are about helping people and meeting them where they are.

Will Cooke: At some point, we just have to put people first. We have to value the sacredness of a human life. Once that’s snuffed out, it’s gone forever. … Why are we going to just sit back and say, “Well, that was their choice. I guess they are just doomed now.” That’s not compassion. That’s not love or caring. That’s not being a fellow human to that person in need. We’re supposed to be there for each other. Period.

Celine Gounder: Not all health professionals are as compassionate as Will. It can be really demoralizing to see the same patients over and over, with the same infections over and over, and worse, after overdose, after overdose. EMTs and many law enforcement officials now carry naloxone in case they run into someone who’s overdosed on opioids and needs saving. But what happens after someone gets naloxone? That’s what we’ll be talking about on the next episode of “In Sickness and in Health.”

Celine Gounder: Today’s episode of “In Sickness and in Health” was produced by Nora Ritchie and me. Our theme music is by Allan Vest. You can learn more about this podcast and how to engage with us on social media at insicknessandinhealthpodcast.com, that’s insicknessandinhealthpodcast.com.

Celine Gounder: If you like what you hear, please leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find out about the show!

Celine Gounder: If you or a loved one needs help, you can reach out anonymously and confidentially to SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP, that’s 800-662-4357. SAMHSA stands for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. You can also find information online at www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov, that’s www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov.

Celine Gounder: I’m Dr. Celine Gounder. This is “In Sickness and in Health.”