“I think really the lesson we need to learn from the past is that there are real fears here, and we may not see those fears as legitimate, but these people do and we should understand what is it that concerns them.” –Nadja Durbach

In Episode 64 of EPIDEMIC, Smallpox and the Origins of the Anti-Vaccination Movement, Nadja Durbach (professor of history at the University of Utah) and Michael Willrich (author of Pox: An American History) dive into the origins of the smallpox vaccine and the history behind vaccine hesitancy.

England suffered recurrent smallpox outbreaks throughout the 19th century. The upper class attributed these outbreaks to miasma, the idea that diseases come from bad odors in the air. Working-class citizens were stigmatized, thought to be spreading smallpox to the rich through air-borne miasmic dirt.

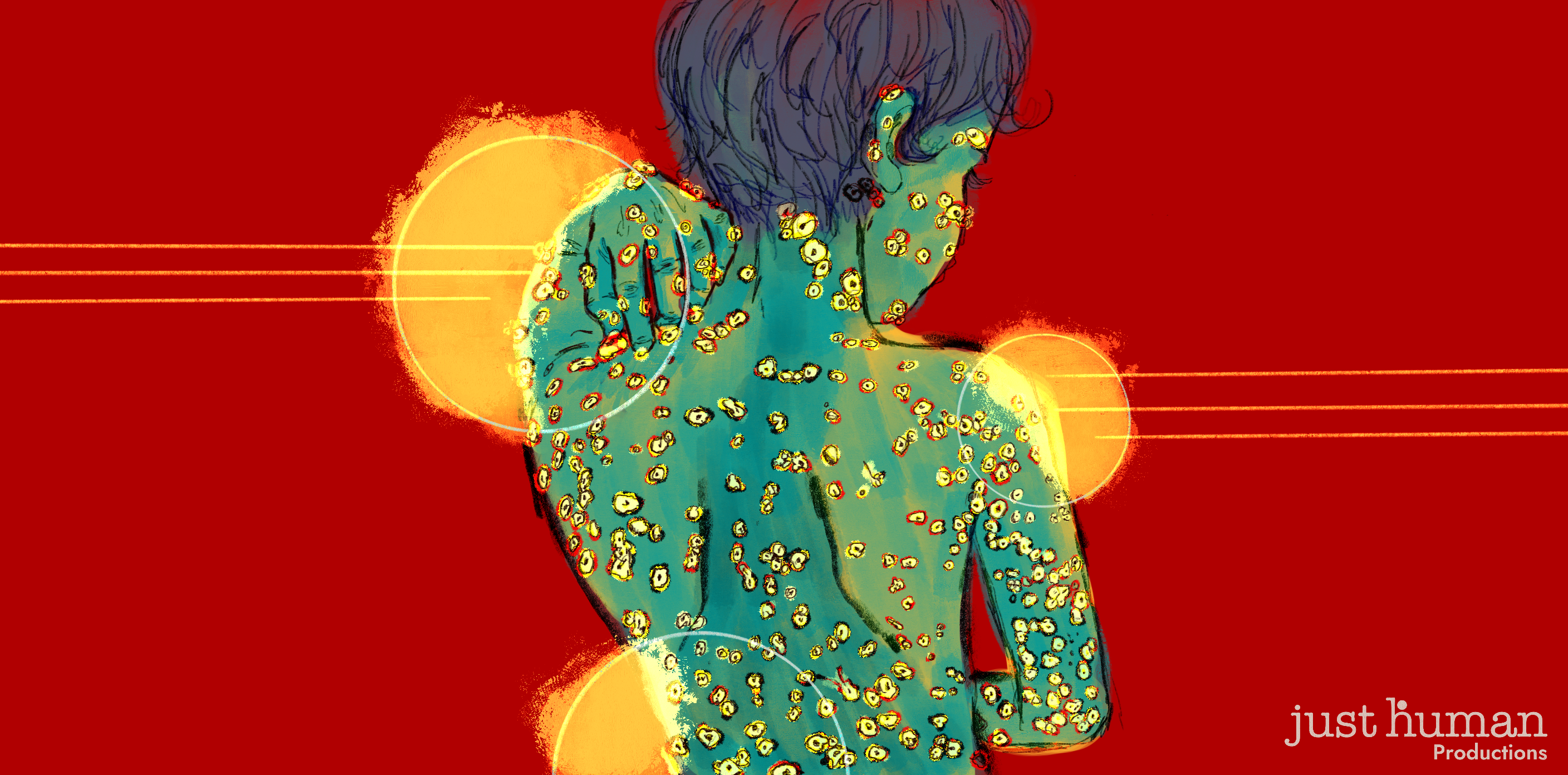

As one in three smallpox patients in England died, the public health threat was urgent. Edward Jenner, a British physician, noticed a crucial connection between cowpox and smallpox: both infections caused pustules that left pockmarks on its victims. It was also commonly believed that dairymaids were in some way protected from smallpox. Jenner set out to test a theory: that infection with cowpox protected against smallpox. He wasn’t the first to try this, but he was the first to study the theory scientifically. Jenner’s first test subject was his gardener’s 8-year-old son, James Phipps. Using a knife dipped in the pus from a cowpox sore, Jenner made small cuts in Phippss’ arm. Phipps developed a slight fever, but the discomfort quickly passed. Jenner then infected Phipps with a dose of smallpox a couple months later, but Phipps remained healthy.

After Jenner had tested cowpox inoculation on several others, he published his findings in a booklet, An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox. Within a couple years, vaccination had spread throughout Europe. The British government deliberated over Jenner’s findings for some time, but in 1840, passed the first of a series of Vaccination Acts.

The Vaccination Acts made vaccinations free of charge and mandatory for all children under fourteen years of age. The poor had to rely on free vaccines from workhouses, while the rich were able to pay for doctors to vaccinate them under sanitary methods. Durbach, describing the unsanitary methods used to vaccinate indigent children, said “…they would take that same knife and they would stick it in the arm of a baby who had already been vaccinated the week before and scoop out the vaccine from that baby’s arm and smear it into the cuts on the next baby…” Unsanitary early vaccinations created fear among working-class citizens, who were forced by law to submit.

This class prejudice took a similar form in the United States. Like England, the U.S. also mandated vaccination, and “virus squads” would show up at working-class homes to force vaccination. Even at the turn of the last century, vaccination methods remained primitive and unsanitary. In addition, the African American community had suffered centuries of abuse and experimentation at the hands of the government and doctors and had good reason not to trust public health authorities. Eventually, officials came to understand that unregulated, unsafe vaccinations were, with good reason, driving working class pushback. In 1902, Congress passed the Biologics Control Act of 1902, establishing a nationwide system for licensing and inspecting vaccines to ensure they were safe.

Currently, the U.S. is experiencing a similar lack of confidence in vaccines. Durbach and Willrich both believe public health officials have a lot to learn from the smallpox epidemic. Willrich points out that “public health officials seem to be very aware to strive to lead through education rather than coercion…” The history of smallpox shows that vaccination mandates can backfire if you don’t address the public’s very real and genuine concerns about vaccine safety. Early vaccination campaigns unfairly targeted groups based on class and race, which also harmed public confidence in vaccines.

Listen to Episode 64 to learn more about the history of vaccination and vaccine hesitancy and look out for upcoming episodes that focus on the different reasons why people may not have confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccines.