The Amazon is the world’s largest rainforest and the most biodiverse place on Earth. At its center, you’ll find not just rare or even undiscovered species (which you might) or acres of scorched earth (which you certainly will, due to the devastating fires of 2019).

You’ll also find, amidst the jungle, the teeming metropolis of Manaus, which sits at the confluence of the Amazon and Negro Rivers. It’s the capital of the state of Amazonas and home to more than two million people, including Felipe Gomes Naveca, a public health researcher and virologist who studies the Covid-19 outbreak there.

He knows firsthand just how devastating the virus can be. “There are at least four people from my team who lost a mother or an uncle or father,” he says. He lost his own father to Covid but returned to work just two days later.

“We don’t have time to cry for our relatives,” he adds. “We have to return to the lab. Maybe when this pandemic is finished, we can rest and think better about this. We are really tired at this moment.”

Since the pandemic began, Brazil has experienced some of the highest rates of Covid-19 on earth, and Manaus residents were infected at terrifying rates –– possibly as high as 75% by fall of 2020. It was shocking.

But for a moment, there seemed to be a possible silver lining to the crisis in Manaus: When so many people have the virus, is “natural herd immunity” next?

Felipe and fellow researcher and physician Ester Sabino discuss what happened in Manaus, why the city was so susceptible to this outbreak, and what it has shown researchers about Covid-19 around the world.

Swift spread, sluggish response

Brazil’s first case of Covid-19 was identified in late February in a patient who traveled from Italy to Sao Paulo. Unfortunately, around the same time, Carnaval — the country’s four-day celebration ahead of Lent — was in full swing.

About seven million people were estimated to have attended Rio de Janeiro’s Carnaval in 2020. But Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsanaro, brushed off the risk the virus posed.

He urged citizens to keep working, criticized masks and pressured public health officials to repeal social distancing restrictions. The virus spread quickly, especially in urban areas. Bolsanaro later contracted the virus himself.

Sound familiar?

Devastating numbers

Before Covid-19 spread globally, Ester Sabino was working with a team from Oxford University to improve Brazil’s ability to respond to outbreaks of infectious diseases like HIV, dengue, and Zika.

Shortly thereafter, they shifted their focus to the novel coronavirus. Tracking the virus was a challenge at first, since testing wasn’t widely available. Brazilian blood banks have a mandate to save samples for six months. Ester and the research team realized they could perform tests on these samples to better track the spread of Covid-19 in Brazil.

They won a grant to perform serological tests, which can find traces of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in blood samples. The presence of antibodies tells us someone has been infected (even if they didn’t get sick). That’s how they could estimate how widely the virus had already spread.

Manaus was one of the first cities Ester’s team studied, along with Sao Paulo.

What they uncovered was puzzling: Manaus seemed to be one of the worst-hit cities in the world. She estimated that about 50% of the population had antibodies in June. By September, that estimate rose to 66%. And by October, the research suggested that 75% of the city had been exposed to the virus.

By contrast, about 30% of Sao Paulo residents had been infected by October.

Manaus’ infection rate is staggering. To put it in perspective, about 20% of New York City’s population was estimated to be infected before the winter surge.

Why did Manaus, a city of two million, experience such a high infection rate compared to the much bigger city of Sao Paulo (pop. 22 million)?

Researchers can’t be certain, but it probably has to do with a particular kind of population density: “The number of people per house in Manaus is higher than the number of people per house in Sao Paulo,” Ester says.

Cell phone data backed up that theory — although people in both cities practiced a similar level of social distancing, the virus is much more transmissible indoors. And with more people living closer together in Manaus, it became a Covid-19 breeding ground.

New variants challenge ‘herd’ immunity theory

In fact, the infection rate was so high in Manaus, some argued that the city would reach so-called “natural herd immunity,” which is achieved when there are too few susceptible hosts to transmit the disease.

This can happen when most of the population has already had the infection or received a vaccine that prevents the transmission of infection It’s unclear whether available Covid-19 vaccines do that.

But that’s not the only reason herd immunity to the virus will likely remain elusive.

In Manaus, the number of cases fell by mid-year. But then they came back –– with a vengeance.

In the middle of December, it was clear “something new” was happening in the state of Amazonas, says Felipe Gomes Naveca. Initially, researchers thought it could be a variant of concern, or VOC, from South Africa or the United Kingdom.

VOCs emerge when a virus spreads too widely over too much time –– it “evolves to a new variant that seems to be more adapted to [infect] human beings,” he explains.

But to their surprise, it was a new VOC, which is now known as P.1. And it circumvents the antibodies Covid survivors build up when they’re infected.

“There is no way to explain what happens in Manaus without thinking that reinfection is probably common,” says Ester.

A new variant –– and a deadly second wave

What happened next was what Felipe calls “the perfect storm”: Rainy weather, resistance to social distancing — especially over the December holidays — and the new, more transmissible variant all added up to a new spike in cases in January.

“We had at least two weeks of total chaos in Manaus,” he says.

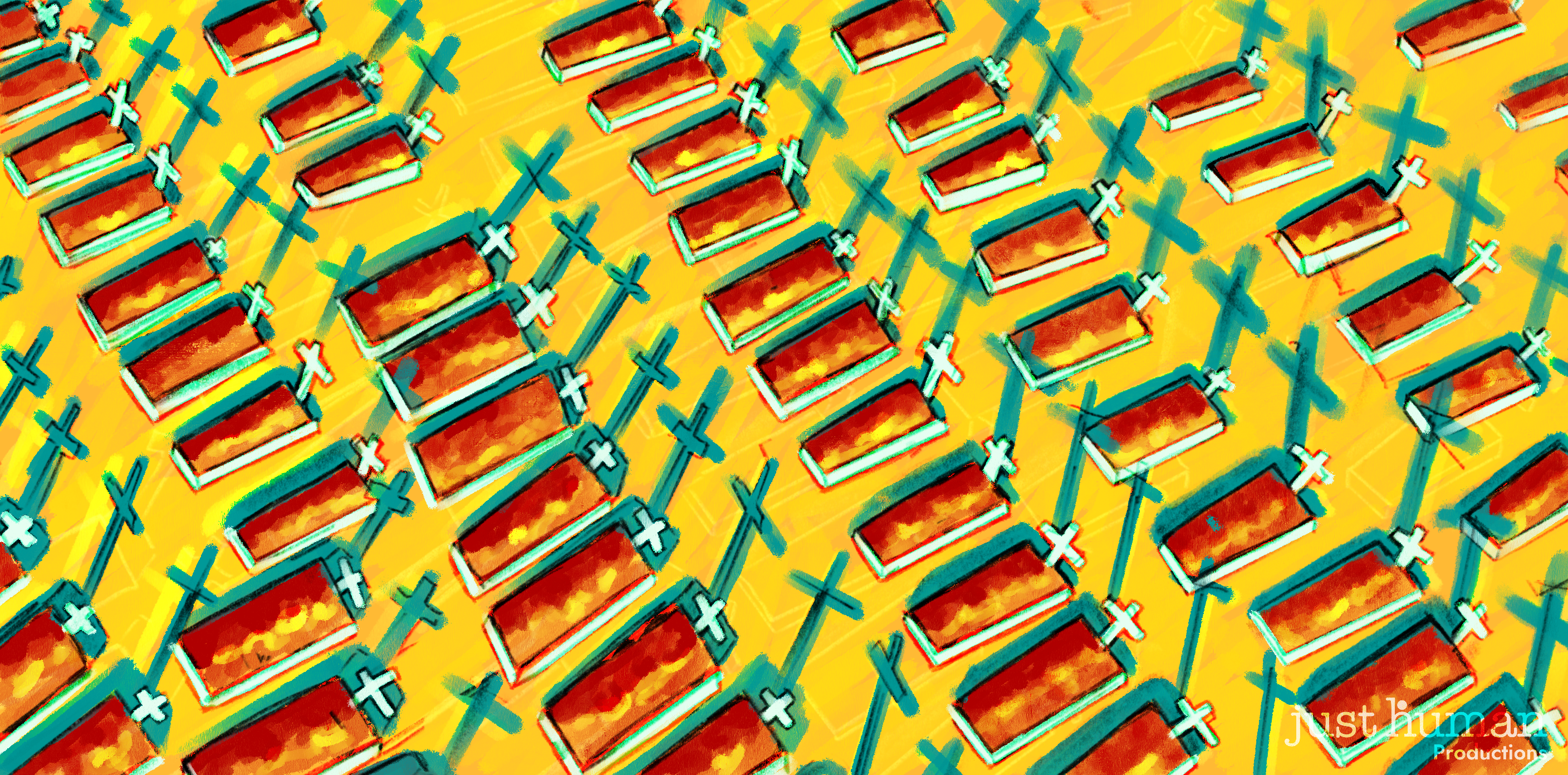

The city’s healthcare system was overwhelmed. Hospitals ran out of beds and oxygen. Some patients in need of ICU care had to be airlifted to other cities –– even as far away as Sao Paulo, which is more than 2,000 miles away from Manaus. At the worst point, there were more than 200 daily Covid deaths in the city.

Now the P.1 variant is spreading across Brazil. And if it takes hold in the southeast of the country, where almost half the country’s population lives, “we will have a big problem,” says Felipe.

That’s worrying, and not just because of population density. The P.1 variant in Brazil has mutations in common with the B.1.351 variant, which was first identified in South Africa. The B.1.351 variant has shown increased resistance to COVID vaccines.

“I believe that we will have some losses in efficacy, but I hope that it is still enough to protect against P.1,” Felipe says.

Recent trials suggest there’s good reason to hope. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found the Pfizer vaccine retained its effectiveness against the UK and Brazil variants. However, both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are less effective against the South Africa variant, generating neutralizing antibody responses that are lower, but still protective.

But the biggest problem right now, says Ester, is that there’s not enough vaccines to go around.

“If there were enough vaccines, I’m sure we would be able to vaccinate everybody very quickly. But the thing is, we don’t.”

Brazil missed several opportunities to order the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines. And although it plans to manufacture the AstraZeneca vaccine in-country, it hasn’t yet been able to get sufficient amounts of the raw materials it needs to do so. For now, it’s relying on what it could buy: the Chinese CoronaVac vaccine, which clinical trials show is effective just about 50% of the time.

The situation in Amazonas is instructive for the U.S. and the rest of the world: Herd immunity isn’t achievable –– at least not in the immediate future –– so we must do everything we can to prevent ourselves, and others, from getting infected.

“I think everybody should be worried and be looking for new variants,” says Ester. “I think it might happen in other places. I think we are just seeing the first ones.”

That’s why we’re going to be living with Covid for some time.

“You cannot just think it’s going away … like magic,” Ester says with a laugh. “It’s not Disneyland.”

This article is based on an episode of EPIDEMIC, a weekly podcast series on the science, public health, and social impact of the coronavirus pandemic, hosted by Dr. Celine Gounder, a practicing infectious diseases specialist, epidemiologist and member of President Biden’s Covid-19 Advisory Board. Subscribe to the podcast through Apple, Spotify, Google, or your preferred podcast app.