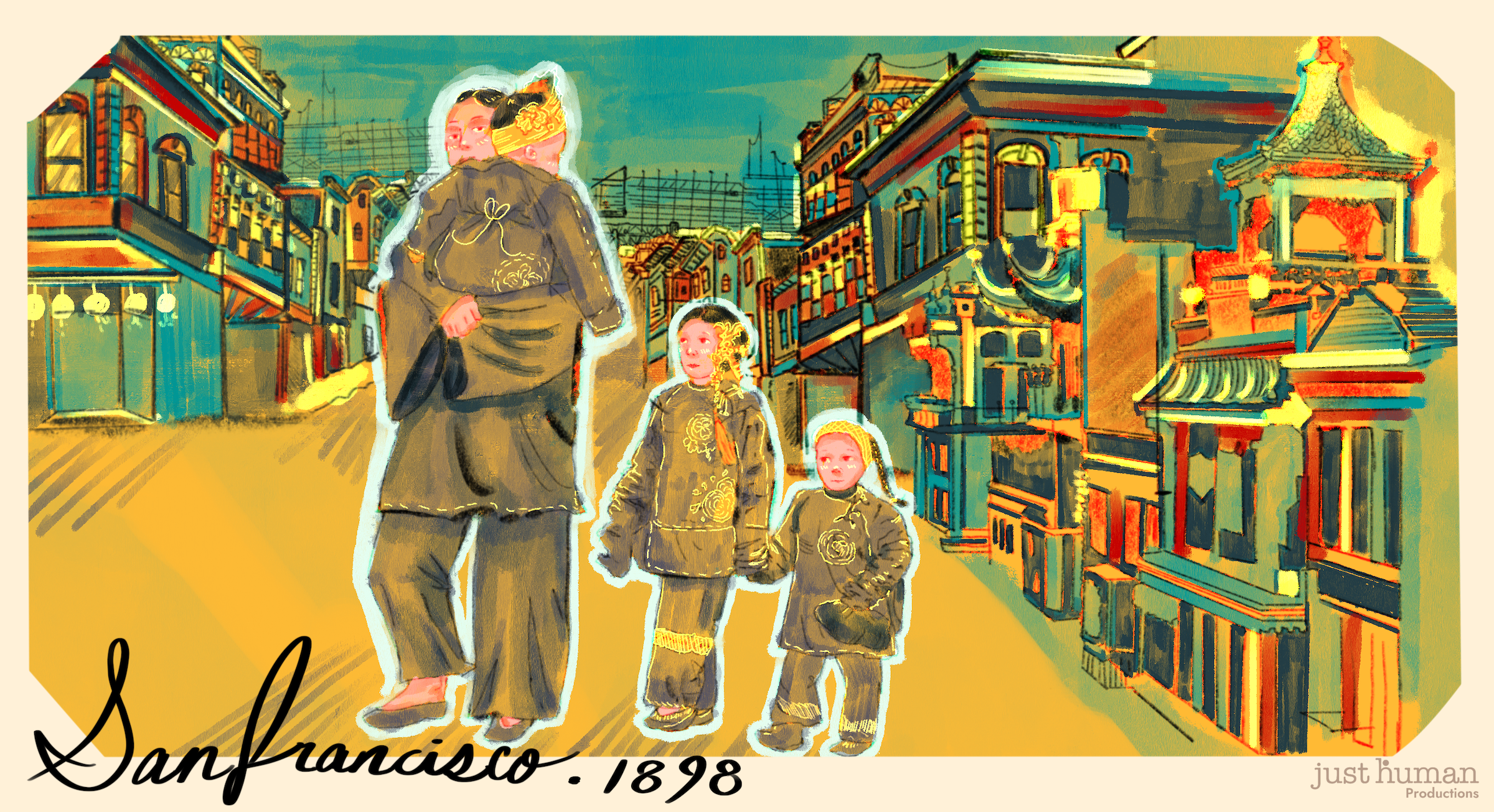

A world interconnected by trade and travel like never before; a grisly illness making its way to the United States from offshore; inaction and denial in government; a widespread distrust of science; fury over quarantines; and a raging xenophobia that made Chinese-Americans scapegoats for a nation’s vulnerability to disease. Welcome to 1900, post-Gold Rush San Francisco, and the arrival of bubonic plague in North America.

This COVID year isn’t the first time an epidemic has torn open rifts in the national fabric — laying bare not only our interconnectedness but also our cultural anxieties, and unraveling tensions over immigration, the economy, science, and our notions of the “other.” Anti-Asian hate crimes have risen over 150 percent in the past year — most visibly, last month in Atlanta, where a gunman killed eight people, six of them women of Asian descent. As we tease apart the threads of anti-Asaian racism and COVID rancor, 1900s San Francisco offers object lessons in the pitfalls and possibilities of pandemic response.

“You can never really analyze a disease solely in a vacuum, in isolation,” says Merlin Chowkwanyun, a historian of public health at Columbia University. “How we respond to disease is, in fact, a mirror and a microcosm of what is going on in larger society.” He notes “a feedback loop between broader social anxieties and how we talk about disease” — one that has whirred throughout the pandemic, and was thrumming, too, at the turn of the twentieth century, when the plague turned up in San Francisco, after killing some 15 million people in China and India in the decades prior.

Within San Francisco, plague was often cast as an Asian disease, says David Randall, a senior reporter at Reuters and author of Black Death at the Golden Gate. Some believed the plague affected only people who ate rice — that meat-eating Americans weren’t susceptible, or that those with European ancestry had “inherited” immunity.

Meanwhile, as the eugenics movement took root, charts and tables of different races ranked groups according to how “fit”or “healthy” eugenicists perceived them to be, deeming some groups genetically superior and others more susceptible to disease. Add to that the concern that Chinese immigrants were disrupting the labor market, taking jobs away from native-born Americans, and a whirlwind of stereotypes gained momentum.

Chinese immigrants had first come to U.S. shores for the Gold Rush, and supplied much of the labor for the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s, often taking on perilous work — blasting tunnels, working amid avalanches — that others refused. Eventually, they made up nearly 90 percent of the Central Pacific Railroad’s workforce. By 1880, 16 percent of San Franciscans were Chinese. Barred from citizenship — and from owning or leasing property — many congregated in San Francisco’s Chinatown, a congested area of about ten square blocks.

In newspapers and public-health records, descriptions of crowded housing, a lack of sanitation, and unfamiliar foods in immigrant communities presented a kind of litany of depravity. Spurious biological notions of race, firmly embedded in American minds, offered an easy way to compartmentalize risk, susceptibility, and blame. As the century wore on, says Chowkwanyun, a belief took hold “that there is something terribly different and biologically different about racial minorities that makes them much more susceptible to developing disease.”

Public health — though it was developing key tenets about the importance of hygiene and urban infrastructure — was hardly neutral when it came to demographics. As urban density had increased following the Industrial Revolution, and cholera and dysentery swept through cities, the “miasmic” theory of disease took hold — the idea that illness was caused by garbage fumes, the stench of sewers, and the general squalor of city life. The Sanitary Movement of the 19th century aimed to clean up cities and educate the public about good hygiene — missions that would remain at the core of public health. But it neglected the structural circumstances that often left poor people in cramped, dilapidated housing without access to basic hygiene, insisting instead that the way to improve public health was by changing people’s habits — creating what Chowkwanyun calls “a rhetoric of blame”

Denial, deceit, and desperation

On March 6, 1900, the first official victim of plague in San Francisco, Wong Chut King, was found, left for dead in the back room of a coffin shop with a telltale swollen black lymph node (or bubo) on his groin. Dr. Joseph Kinyoun, San Francisco’s chief quarantine officer, quickly ordered Chinatown roped off, leaving residents without provisions or any sense of what might come next, and leaving much of San Francisco without the labor it had come to depend on. (Meanwhile, cases of plague outside of Chinatown were consistently misdiagnosed, so reluctant were doctors to believe that plague had arrived.) San Franciscans greeted the quarantine with skepticism, dismissing rumors of plague as another way for the health department to justify taxes. City officials, desperate to promote an edenic view of California, and fearful that the local economy would collapse if word of plague spread, derided Kinyoun for scaremongering. Governor Henry Gage organized a state-wide news blackout.

Within Chinatown, residents grew desperate: “People started climbing into the sewers, started climbing across rooftops and doing anything they could to get out of the quarantine zone itself,” says Randall. Kinyoun tried to forcibly inoculate residents with a serum said to protect against the plague, and pressed for all residents of Chinatown to be moved to an island in the San Francisco Bay.

The plague became “a racial question,” says Randall. “It was an economic question. It was an ‘us vs. them’ question. And it was a question of, ‘How much can we believe in science? How much can we believe in something that we can’t see with our naked eye?’” Kinyoun, though firm in his scientific grounding, was draconian in his application of it, and racist in his relentless focus on Chinatown: “He was this brilliant man and he did many things to move science forward,” says Randall, “and he probably could have saved more lives if he had been able to move his own social ideas … forward as well.”

Ultimately, says Randall, word got out about plague in California: Other states began refusing Californian goods; passengers got off California-bound trains in Denver or Portland and turned around; grocers boasted of banning California produce. This pressure from other states persuaded California to take the outbreak seriously.

Kinyoun was essentially run out of town, with a state senator even calling for his death. His replacement, Rupert Blue, was less scientifically eminent, but far more affable: He forged relationships with people and organizations in Chinatown, opened an office and lab there, and hired Chinese translators and paid them equally — a radical move at the time.

What prevails, and what endures

“You really need two things in a medical crisis,” says Randall. “You need the hard science — but that won’t really be effective unless you have that soft science of persuasion and trust and community. Blue — well, that was his genius.” Blue implemented sanitation measures that we now take for granted — concrete sidewalks, rat-proof trash cans, and extermination of the flea-infested rats that were spreading the disease. “Public hygiene in the US was because of this fight against plague.”

But all this took time. In the end, says Randall, plague was contained — and millions of lives were saved — not just because of quarantines or concrete sidewalks, but also because of an anatomical difference in the local rat flea, which led to San Francisco fleas injecting less plague bacteria in their bites.

A flea, a rat, a ship, a distant harbor: Bit by bit, the world was coming together — and in those same connections were not only the bacteria of plague, but the vitriol of xenophobia, nativist fury, economic fear, and a rhetoric of blame in public health. Over a century later, the same anxieties have roiled national discourse, snarling the response to COVID and upending individual lives.

“Some of these tropes do endure,” says Chowkwanyun. “You certainly see this today. Questions about whether Chinese people in the United States are more likely to spread coronavirus, rhetoric of blame against Chinese people writ large, rather than the Chinese government specifically.”

Toby Chow, director of Justice is Global, an organization working for structural economic reform, has called for greater US-China collaboration during the pandemic, as well as a deeper investment in international public health and workers’ rights. In his own life, having lived and worked in Chicago for 15 years after immigrating from Canada, he’s found himself “afraid of my fellow Chicagoans” for the first time. “And it’s really just a devastating feeling.” The anti-Asian sentiment of the pandemic is “something very different to anything we’d experienced before,” he says.

But as we find our way forward, Chow insists one thing is clear: “This pandemic is showing us … that all human life all around the world is deeply interrelated. And none of us is going to be safe and healthy unless all of us are safe and healthy.”